Once in Every Three Years: The Triennial Meetings of the Society of the Cincinnati

This article is adapted from “Once in Every Three Years” by Ellen McCallister Clark and Jack D. Warren, Jr., published in Cincinnati Fourteen 46, no. 2 (Spring 2010): 66-81.

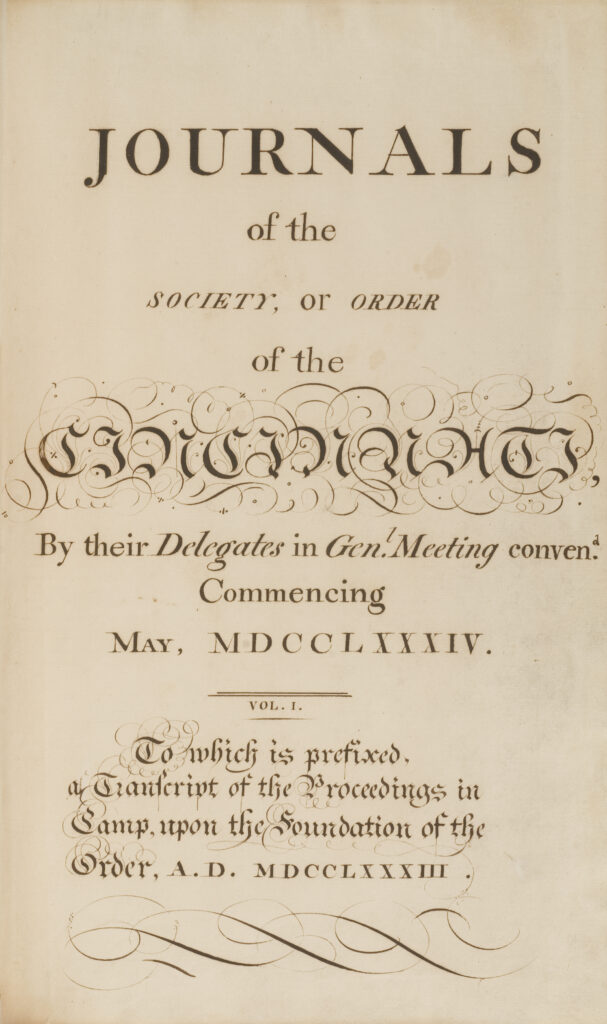

The Society’s Institution, adopted on May 13, 1783, directs that delegates to the General Society will meet the “on the first Monday in May, annually, so long as they shall be necessary, and afterwards, at least once in every three years.” The first general meeting convened in Philadelphia on May 4, 1784, and lasted two full weeks. Since then, with just a few gaps in the early nineteenth century, delegates from the constituent societies have gathered as a body at least every three years. While the Society’s fortunes have ebbed and flowed with the times, there has been a remarkable continuity of purpose as each generation has carried forward with clarity and dedication the original mission of the founders—to perpetuate the memory of the achievement of American independence.

The Challenge to the Institution, 1784-1799

The 1784 meeting brought a challenge to the basic foundation of the Society that would not be completely resolved for sixteen years. Concerned over widely circulating criticism that the Society would create “a race of hereditary patricians” antithetical to the ideals of the new republic, President General George Washington proposed amendments to the year-old Institution that would abolish the hereditary provisions and essentially devolve all power and decision-making to the constituent branches. The proposals were fiercely debated and went through three rounds of drafts in committee. One provision that was re-introduced in the final version called for the Society to continue to meet triennially, but only “to regulate the distribution of surplus funds.”

The debate over the Institution was complicated by the news of Louis XVI’s approval of the establishment of the French branch of the Society—delivered to the 1784 general meeting in person by Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, who had recently returned from a Society-sanctioned trip to France. Major L’Enfant also presented the first issue of gold Eagle insignias, whose manufacture he had overseen in Paris, as well as a special gift for Washington: an Eagle set in diamonds and other precious stones sent by Admiral d’Estaing “in the name of all the French Navy.” L’Enfant’s arrival was a keen reminder of the international interest in the matters under deliberation at the meeting. In the words of one New York delegate, “Our allies alone have saved the society.”

Finally, as Washington presided, a majority of the delegates voted in favor of the amended Institution, the text of which was to be sent to each of the constituent branches of the Society for approval. At the conclusion of the 1784 meeting, Washington was reelected president general, as he would be at each of the subsequent Triennial Meetings for the remainder of his life.

Washington never again presided over a Society meeting. In October 1786 he sent out a circular letter calling delegates to the Triennial Meeting to take place in Philadelphia in May 1787, but wrote that “It will not be in my power…to attend the next General Meeting; and it may become more and more inconvenient for me to be absent from my Farms, or to receive appointments which will divert me from my private affairs.” But the events of history intervened, and Washington answered another call to travel to Philadelphia in May—to preside over the convention that would create the United States Constitution. He explained his conflict of duties in a letter to Henry Knox, which was read before the general meeting. Washington’s diary reveals that on May 15 he took time to dine with members of the Society who were still meeting in the city.

The ratification of the United States Constitution and George Washington’s election as president of the United States seem to have defused much of the public concern about the Society. Washington recognized this in a message he sent to the delegates at the Triennial Meeting in May 1790: “The candor of your fellow-citizens acknowledges the patriotism of your conduct in peace, as their gratitude has declared their obligations for your fortitude and perseverance in war. A knowledge that they now do justice to the purity of your intentions ought to be your highest consolation, as the fact is demonstrative of your greatest glory.” While the Society continued to meet at least triennially through the 1790s, there was never a quorum of delegates represented and almost no formal business was conducted. Following George Washington’s death on December 14, 1799, the Society convened a special meeting in Philadelphia in May 1800. Senator William Bingham, an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Society, read a testimonial of respect to the memory of the first president general. Even more significant to the future of the Society was the conclusion of a committee appointed to review the Society’s records relative to the status of the amended Institution: “That the institution of the Society of the Cincinnati remains as it was originally proposed and adopted by the officers of the American army, at their cantonments on the banks of the Hudson River, in 1783.”

The Founders Carry On, 1800-1847

Alexander Hamilton was elected president general at the 1800 meeting. In recognition of his election, Martha Washington sent him her husband’s Diamond Eagle. Hamilton did not preside over a Triennial Meeting before his untimely death from wounds sustained in a duel with fellow New York Society member Aaron Burr in July 1804. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina succeeded Hamilton as the next president general. Hamilton’s widow, Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, in turn, presented the Diamond Eagle to General Pinckney, expressing to him her hope that it would become the permanent badge of the office of the president general. The proceedings of the Triennial Meeting of 1811 record the Society’s formal acceptance of Mrs. Hamilton’s gift of the Diamond Eagle.

Remarkably, original members of the Society served as president general until 1847. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney was president general for twenty years and was followed by his brother Thomas Pinckney in 1825. Aaron Ogden of New Jersey was elected in 1829, Morgan Lewis of New York succeed him in 1839, and upon Lewis’s death in 1844, the Diamond Eagle and office went to his fellow New York Society member, William Popham.

Popham, who was ninety-two years old when he was elected, was keenly aware that he was likely to be the last veteran of the Revolution to hold the office of president general. Concerned that the younger members of the Society “are but slightly acquainted” with the history of the Society, he composed an address on the subject that was read before Triennial Meeting of 1844. The Society of the Cincinnati was, he wrote, “the Alma Mater of the great and most resplendent empire that the world has ever seen.”

The Society Reformed, 1848-1869

William Popham died on September 25, 1847. In November of the following year the Society convened in Philadelphia and elected as his successor Henry Alexander Scammell Dearborn. The son of original member Gen. Henry Dearborn of New Hampshire, he was the first hereditary member to hold the office of president general. Charles S. Daveis of the Massachusetts Society was assigned the duty of conveying the Diamond Eagle to the new president general, which he did on December 14, 1848. Noting the coincidence that the presentation had taken place on the anniversary of George Washington’s death, Dearborn wrote, “I consider myself highly honored in being elevated to the exalted station, which was first occupied by the illustrious WASHINGTON, & am most grateful for the respectful confidence which the members of that venerated Institution have evinced in my character & abilities.”

The election of Henry A. S. Dearborn launched a period of reform for the Society. Born in 1783, the year the Society was founded, Dearborn made expanding hereditary membership the primary focus of his tenure as president general. By 1848, only six of the original fourteen constituent branches of the Society were in operation—Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and South Carolina—and each was struggling with dwindling membership. Without action, Dearborn warned, the Society “will cease to exist within a third of a century.”

The next Triennial was held in New York City in May 1851. Significantly, it was only the second time since 1784 that a general meeting had not convened in Philadelphia, reflecting Dearborn’s interest in broadening opportunities for members’ involvement. The major business of the meeting was the passage of an “ordinance relative to the succession and admission of members” which would allow the extension of membership to all male descendants of each generation (as was already being practiced in South Carolina), as well as the admission of descendants of eligible officers of the Continental Line who had never joined the Society themselves. The secretary general was ordered to have fifty copies of the ordinance printed, and it was sent to the six surviving constituent societies for ratification. Dearborn, however, would not live to see the process through; he died in Portland, Maine, just two months later on July 29, 1851.

The vice president general, Hamilton Fish, who was then governor of New York, took over the planning for the next Triennial, which was to be held in Baltimore in May 1854. Fish had played a key role in drafting the membership ordinance, and his legal and legislative background is evident in the committee’s report analyzing the “founders’ intent” in the clauses about the succession of membership in the Society’s Institution. By the time the 1854 Triennial convened, Fish had been elected to the United States Senate, but his new duties in Washington did not diminish his involvement in the meeting that would prove to be a turning point for Society membership. As expected, Fish was elected president general, an office he would hold for the next four decades.

For the first time since 1784, delegates from all existing branches of the Society were present at the 1854 meeting. The ordinance on membership had received the formal approval of only two of the six constituent societies, and it went back into committee for modification. In the new version, the provision to extend eligibility to membership to all direct male descendants was dropped and the authority of the constituent societies to regulate admissions was asserted, but the Society resolved that “it would not object” to the admission of male descendants of any officer who would have been eligible to membership by virtue of his rank and length of service. The resolution, which would come to be known was the Rule of 1854, passed unanimously (and was finally ratified by the constituent societies two years later), effectively doubling the potential eligible lines for membership. In his closing remarks to the 1854 Triennial delegates, President General Fish congratulated them on their auspicious vote that would ensure the Society’s future:

The interest in the Society which the presence of the heroes who formed it gave to its meetings has gone—their virtues, their memories, their friendships, the principles which they asserted, remain to constitute its interest. These are now in our keeping; and our Institution is henceforth to be maintained by the emulation of their virtues, the reverence of their memories, the adoption of their friendships, and the advocacy of their principles. It is for us to show that the work which they did was not in vain; the past is theirs, and has been well done—the present is ours, full of hope and of promise; and when the present comes, as it soon will, to be the past, may our sons say that it, too, was been well done.

Larger events in the nation would soon test the Society’s renewed resolve to its mission. By the time of the Triennial Meeting of 1860, the national unity, to which the Institution is dedicated, was much in doubt. The South Carolina delegation did not attend the 1860 meeting held in Philadelphia, although it sent a message of its “great regret,” and neither South Carolina nor Maryland was represented at the Triennial Meeting that convened in New York City in May 1863, in the middle of the Civil War. The minutes of this meeting are silent on any political discussion, but at a dinner for the officers and delegates hosted by the New York State Society, a toast was offered to “Our sister societies of the Cincinnati… Dear to us, every one of them, in the memories of the Past, in the Hope of the Future. Momentary estrangement does not destroy Fraternal Affection.”

The Society Revived, 1872-1914

Relations between the northern and southern state societies rebounded quickly following the end of the Civil War. The South Carolina delegation was back in attendance by the 1869 Triennial Meeting, and in 1872, South Carolina member James Simons was elected vice president general. At his invitation, the Society held its 1881 Triennial Meeting in Charleston, South Carolina.

Looking ahead to the Society’s centennial anniversary in 1883, the delegates at the Charleston Triennial authorized the creation of a commemorative medal, to be sold by subscription through the constituent societies. The centennial medal, which could be ordered in gold, silver, or bronze, measures just under two inches in diameter and bears the Society Eagle with the dates 1783 – 1883 on its obverse. The reverse is designed with a border of laurel and oak leaves surrounding a blank space in which the name of a member and his propositus could be engraved.

From the beginning of his tenure, President General Fish had taken an active interest in documenting the Society’s history—gathering past minutes of its meetings, identifying the eligible lines for membership, and locating the archives of the constituent societies. The ultimate purpose of this work was to encourage the revival of the eight dormant branches of the Society. A report recommending guidelines for the reinstitution of the disbanded constituent societies and their readmission to the Society was entered into the minutes of the 1872 Triennial Meeting.

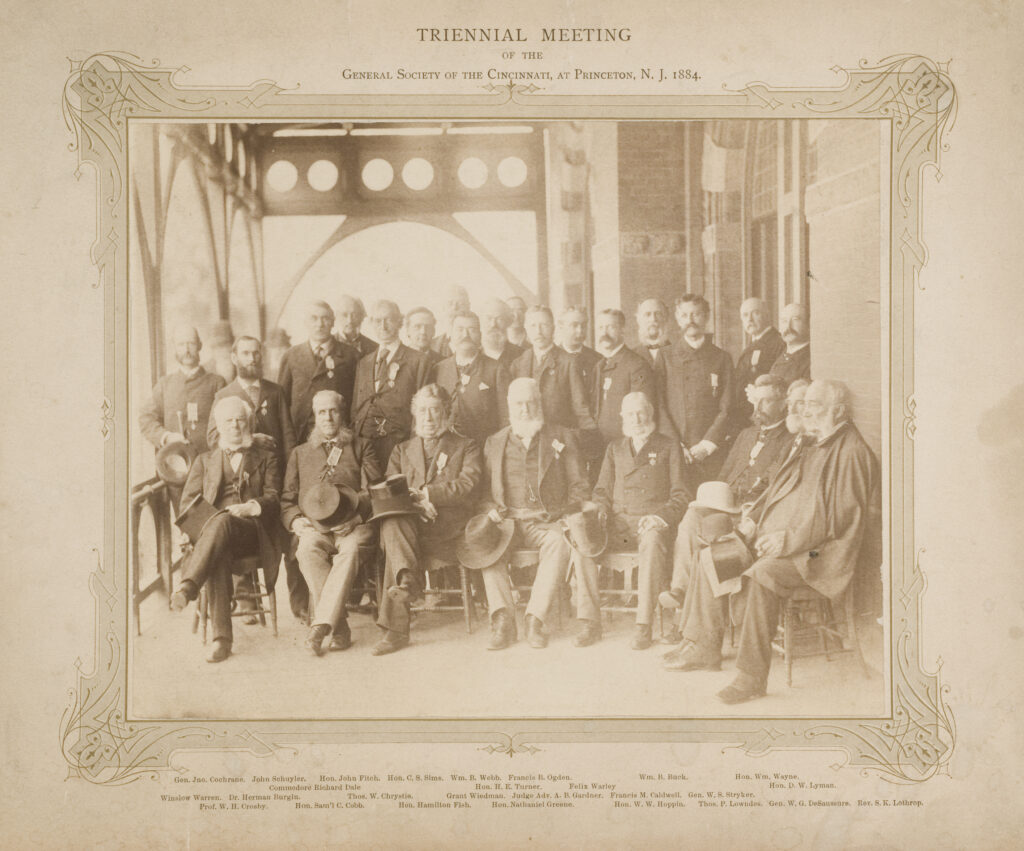

The Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was the first of the dormant branches to be reinstituted. Following a reorganizing meeting in Providence in 1877, four representatives of the Rhode Island Society carried their petition to the Charleston Triennial in 1881, and, following a long discussion on the floor, won readmission to the Society. At the next Triennial, held in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1884, a full delegation of Rhode Island members was in attendance. Not only was their invitation to host the 1887 Triennial in Newport accepted, one of their most ardent and active members, Asa Bird Gardiner, was elected secretary general.

Gardiner, who would serve as secretary general until his death in 1920, played a leading role in the revival and readmission of the seven remaining dormant branches—the Connecticut Society was readmitted at the Triennial of 1896; Virginia in 1899; New Hampshire, Delaware, and North Carolina in 1902; and Georgia in 1904. He took a particularly active interest in research relating to the identification of the eligible lines for membership in the French Society, although he did not live to see the reestablishment of the Société des Cincinnati de France as a constituent branch of the Society, which took place on December 31, 1925.

Hamilton Fish served as the Society’s president general for thirty-nine years, the longest tenure of any to hold that office. His declining health prevented him from attending the Triennial of 1893, held in Boston, but he sent a message to his “dear Brethren” of the Society urging the states to adopt a uniform rule as to the qualifications of applicants for admission. It fell to Secretary General Gardiner to inform the membership of the death on September 7, 1893, of their venerable president general Hamilton Fish, “who, as the honored successor of Washington, Hamilton, the Pinckneys and Ogden in this high office has, since 1854, presided with such distinguished ability over the affairs of the Order.” Indeed, Fish had joined the Society at its lowest ebb of membership, and he had left it well on its way to a complete revival.

William Wayne, a great grandson of Gen. Anthony Wayne, was elected the next president general at the Triennial Meeting in Philadelphia in 1896. He served until his death in 1902 and was succeeded by Winslow Warren of the Massachusetts Society.

Guiding the Growing Society, 1917-1947

The United States had just entered World War I when the Society met in Asheville, North Carolina, for its Triennial Meeting of 1917. Although the Society as an institution had rarely spoken out on world events in the past, the delegates adopted a resolution in support of the war effort: “Remembering that it was the aid of France that made the United States a nation, we welcome the opportunity to repay the debt which was then incurred and to help a people whom we love and admire.”

Winslow Warren served as president general for twenty-eight years, overseeing a period of slow but steady growth in Society membership and activities. Following Warren’s death in 1930, John Collins Daves of the North Carolina Society was elected president general at the Philadelphia Triennial of 1932.

In the 1920s the growing Society began seeking a place in which to establish a national headquarters. Its quest was finally answered in 1938 with a most significant gift. Following the wishes of her husband, Larz Anderson, a devoted member who had died a year earlier, Isabel Anderson presented to the Society Anderson House, the couple’s elegant Neoclassical mansion in Washington, D.C. Within a year of the transfer of the deed, the Society began using the building for offices and meetings and opened a portion of the house as a public museum. To honor Mrs. Anderson’s generosity, the delegates at the 1938 Triennial made her an honorary associate of the Society, granting her the privilege of wearing her late husband’s Eagle.

To honor Isabel Anderson’s generosity, the delegates at the 1938 Triennial made her an Honorary Associate of the Society, granting her the privilege of wearing her late husband’s Eagle.

The Daves administration included two of the Society greatest twentieth-century leaders—Bryce Metcalf and Edgar Erskine Hume. Building upon the work of earlier members, Metcalf researched and compiled a complete roster of members of the Society through time, as well as the eligible lines created by the Rule of 1854. Published by the Society under the title Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati 1783-1938, Metcalf’s work remains a standard source for membership research.

Succeeding Daves as president general in 1939, Metcalf led the Society through the years of World War II. During the early 1940s the Society hosted a number of fundraisers and other events related to the war effort, and in January 1942, its leaders agreed to lend Anderson House to the U.S. Navy for use as offices during the war. The Society had planned to hold its 1944 Triennial Meeting at Anderson House, but with the Navy still in residence, the meeting was moved to New York City. It was not until May 1947, almost a decade after the Society had acquired its fine new headquarters, that a Triennial Meeting convened at Anderson House, which had been turned back over to the Society’s custody in December 1945.

If Metcalf was the authority on membership, Edgar Erskine Hume was the most prolific chronicler of the Society’s history, publishing more than fifty books and pamphlets on the subject. A physician and career army officer, he was a member of the U.S. Army Medical Corps during World War I and the years following. The minutes of the 1944 Triennial note with great respect his absence because of his service in Europe, where he was chief of the Allied Military Government and assistant chief of staff of the Fifth Army. Among his many military awards were three Distinguished Service Medals, five Silver Stars, four Purple Hearts, and the Legion of Merit. Having served the Society as a general officer since 1932, Hume became president general in 1950, but he died only two years later.

Triennial Meetings of the Modern Society, 1950-present

A major change in the Society's governance took place at the Charleston Triennial of 1950. Bryce Metcalf, president general since 1932, retired voluntarily, and the delegates passed a resolution limiting the offices of president general and vice president general to no more than two consecutive terms of three years each.

This change in governance fundamentally changed the nature of Triennial Meetings. Up until 1950, Triennials were the chief business meetings of the Society. Since 1950 they have marked transitions in the leadership of the Society—opportunities to express appreciation to the outgoing president general and other retiring officers, and to inaugurate the new president general and launch his administration.

This change in the nature of Triennial Meetings accelerated another change that had been gradually overtaking the Society. Through the first decades of the twentieth century, much of the routine business of the Society was done by the standing committee—a body created to wield the authority of Triennials in the three years between meetings. From the late 1930s, the Society’s tangible assets—chiefly Anderson House—were managed by a legally separate institution, a tax-exempt corporation governed by an independent board of directors consisting of the members of the standing committee. Triennial Meetings, increasingly, were reserved for major decisions and changes in the governance of the Society.

The 1953 Triennial Meeting was held in Philadelphia and elected Richard Hooker Wilmer of the New Jersey Society as the first in what would be a succession of one-term presidents general. That meeting also ventured as far as any Triennial Meeting has into contemporary politics—an arena the Society had assiduously avoided since the controversies surrounding its founding. Delegate Hamilton Fish of the New York Society—grandson and namesake of the Society’s longest serving president general—presented a resolution condemning “the evil conspiracy of world communism” and those within the United States “who advocate the overthrow of our republican form of government by force and violence.” The resolution was vigorously debated, and its language somewhat altered, but the meeting ultimately adopted it, urging “Congress…to investigate all communist and subversive activities…and to use every legitimate and constitutional means to drive them out of the Federal, State, and other instrumentalities of government.”

The 1953 Triennial in Philadelphia and the 1956 Triennial in Newport were elegant affairs, but they were eclipsed by the 1959 Triennial Meeting, the first ever held in Paris. A special train was reserved to carry the American delegates from the port of Le Havre to Paris, where they were met by a formal delegation of the French Society. The occasion was captured on film and the welcoming ceremony broadcast the next morning over French radio. During the Triennial, the delegations were elegantly entertained—at the Hôtel de Ville, Versailles, the spectacular gardens of the Paris Chamber of Commerce, the Hôtel des Invalides, Vaux-le-Vicomte, the palace at Fontainebleau, and several of the finest restaurants in the city. The Triennial Meeting of 1959 set a standard of grandeur to which all subsequent Triennials have strained to meet. The succeeding Triennial Meetings—Baltimore in 1962, Boston in 1965, Princeton in 1968, and Wilmington, N.C., in 1971—made progressive improvements in the governance of the Society and added to the traditions now associated with Triennial Meetings (such as the recognition of fifty-year members of the Society, which began in 1971).

Triennial attendance has grown significantly in the modern era. As recently as the 1970s, several state societies did not send a full delegation of five delegates and five alternates, but since 1980 Triennial delegations, with few exceptions, have been completely filled, and the number of other attendees—committee chairmen, association presidents, and other officials—has gradually increased. But the size of the meetings has not kept pace with the growth of the membership. In 1950 the Society had 1,679 members. By 1968 the total reached 2,404, surpassing the number of original members for the first time. In 1980 the Society had 3,054 members. Today the total membership numbers over 4,500 and is steadily increasing. One member in fifteen attended the 1950 Triennial. The capacity of recent Triennials has limited official participation in the business meetings to about one member in twenty, but since 2013 all members are invited to attend some Triennial events, including the installation of the new president general at the traditional Triennial ball.

The challenges to the host societies have grown as well. Prior to the landmark Triennial Meeting in Paris in 1959, Triennial planning began a year or eighteen months in advance. The planning time needed to mount a Triennial has grown steadily over recent decades. The spectacular Paris Triennials of 1974 and 2001 each inspired their generation of Triennial hosts and set standards for elegant entertaining, requiring hosts to begin planning as much as nine years in advance, with continuous work beginning more than three years ahead of the events. Despite the pomp and ceremony and the tradition of elegant hospitality by the host society, Triennial Meetings remain an essential aspect of the governance of the Society and continue to provide leaders of the Society with a rare opportunity to gather and enjoy the fellowship founded by George Washington and his officers. They provide now, as they did two centuries ago, an opportunity for members to renew their bonds of affection and to celebrate their “one Society of Friends.”