The Society of the Cincinnati’s two principal emblems of membership, the Eagle and the diploma, were designed by Pierre-Charles L’Enfant (1754-1825) soon after the Society was founded in 1783. Both were first described in a letter from L’Enfant to General Steuben, the acting president of the Society, on June 10, 1783. Carefully seeking to balance the Society’s republican ideals with the traditions of European military orders, L’Enfant proposed that the Society adopt an “Order,” or badge, in the form of the American bald eagle bearing the emblems of Cincinnatus described in the Institution. In addition, L’Enfant suggested that every member be given a silver medal and a “diploma of parchment” stamped with the insignia. He enclosed with his letter drawings of each of these proposed emblems.

It is not surprising that Steuben turned to the ambitious young Frenchman for advice. L’Enfant had arrived in America in 1777 at age twenty-three to volunteer his services to the American forces. His aptitude for drawing and design earned him an appointment as captain of engineers. As a member of Steuben’s staff, he drew the illustrations for Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, the first authorized manual of the American army, published by an Act of Congress in 1779. L’Enfant went on to serve with distinction in the South, rising to the rank of major before the war’s end. An early and enthusiastic member of the Society, he signed an early copy of the Institution along with several other officers of the Corps of Engineers on May 24, 1783.

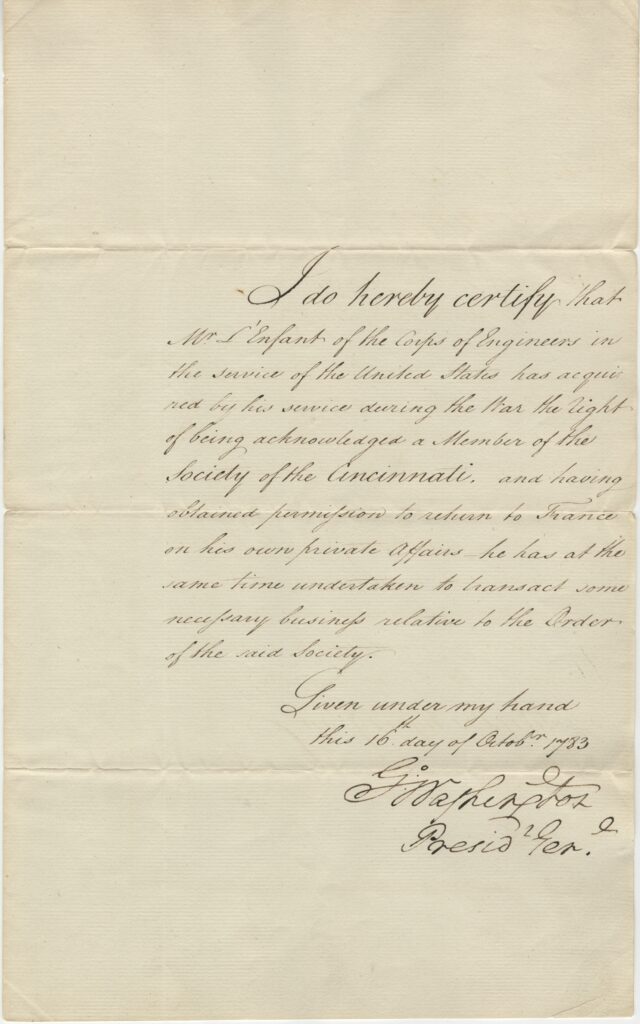

L’Enfant’s proposals for the Eagle, medal, and diploma were adopted on June 19, 1783, by the officers of the Society, who also accepted his offer to carry the “designs into execution.” Believing that the work would be best accomplished by French artisans, L’Enfant made plans to travel back to his native country. Significantly, what could be considered the earliest certificate of Society membership is a handwritten testimonial signed by George Washington stating that L’Enfant was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati “charged with the execution of important business of said Society” while traveling in France.

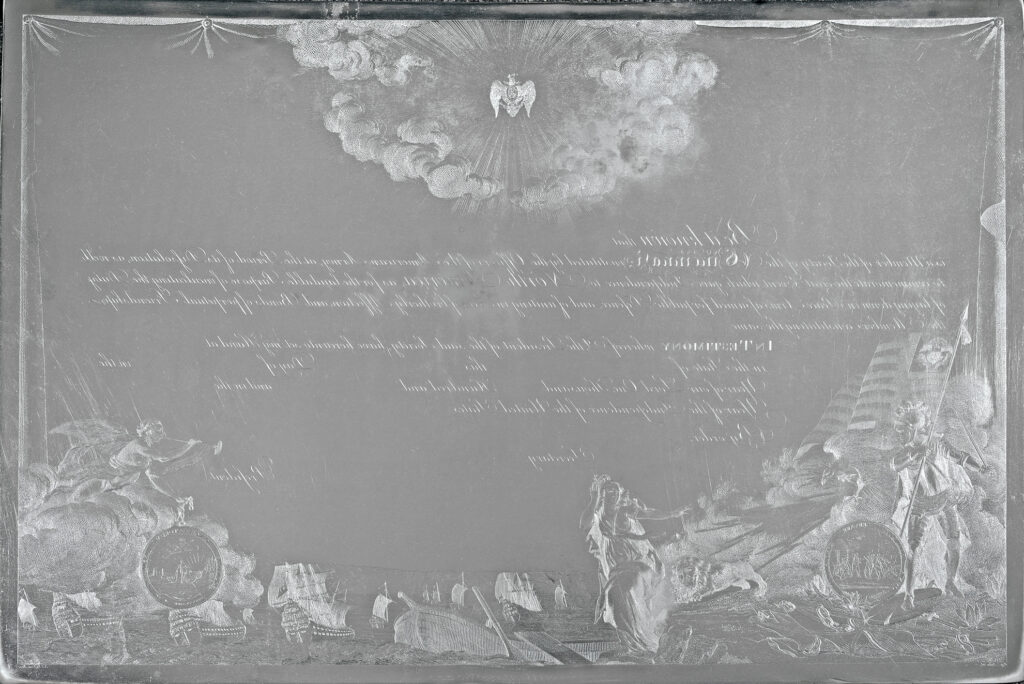

L’Enfant departed from Philadelphia in early November 1783 aboard the Continental Navy ship George Washington. He arrived in France on December 8 and immediately went to work on Cincinnati business. Before two weeks were out, he had secured the approval of Louis XVI for the admittance of French officers to the Society. He also moved ahead in commissioning the manufacture of the Eagles and a copperplate for the diploma.

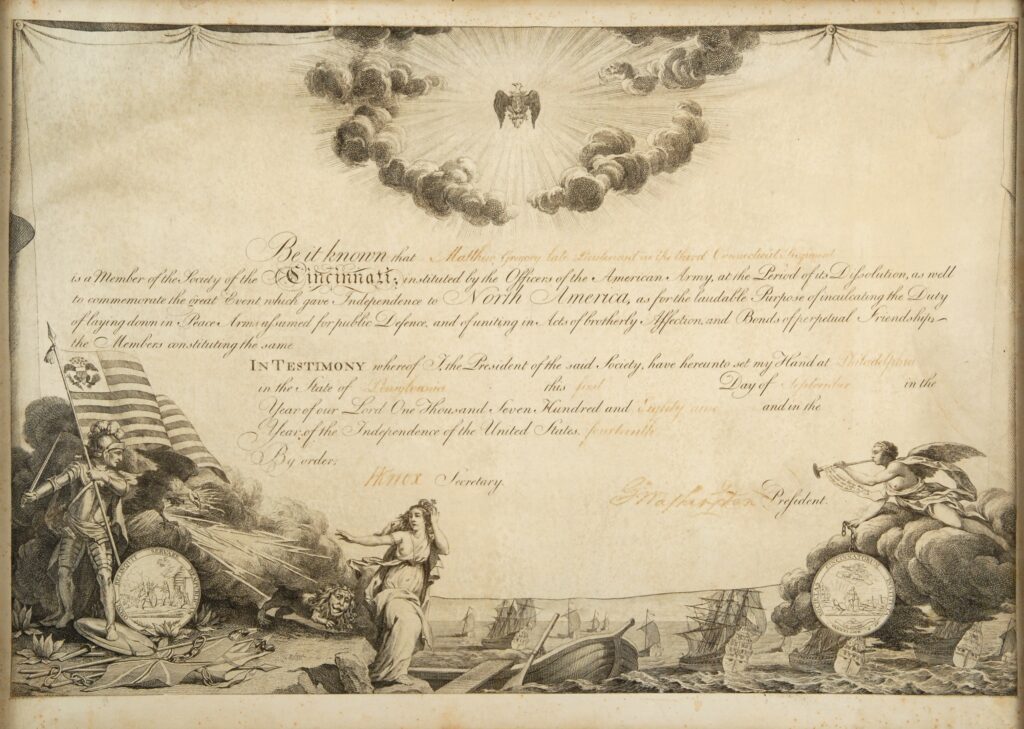

Before L’Enfant left America, Henry Knox had seen and approved his original drawing of the diploma, calling the design in a letter to Washington a “noble effort of genius.” Nevertheless, L’Enfant engaged the services of Augustin-Louis La Belle (1757-1841) to redraw his concept so that it could be accurately rendered as a copperplate engraving. La Belle, a member of a celebrated family of artists, had only recently returned to Paris from his studies in Rome, where his work had earned him the second Grand Prix in 1782. Following his Cincinnati commission, he would go on to a distinguished career as an artist, eventually succeeding his father as superintendent of the Gobelin factory. For the engraving of the copperplate, L’Enfant turned to one of the foremost engravers of the day, Jean-Jacques Le Veau (1729-1786). Originally from Rouen, Le Veau had studied under the noted engravers La Bas and Le Mire, eventually establishing himself as one of the recognized masters of the field. Together, the talents of L’Enfant, La Belle, and Le Veau produced a finished work of great artistic merit. Its powerful iconography was vividly described by the nineteenth-century antiquarian Benson J. Lossing in his Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution:

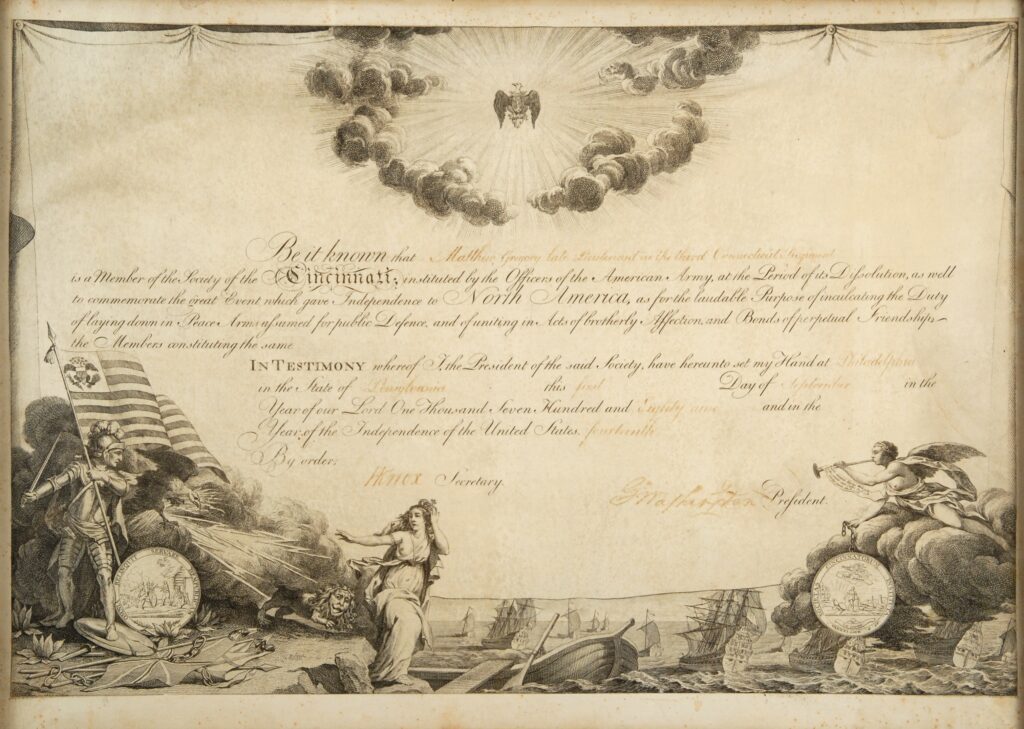

The design represents American Liberty as a strong man armed, bearing in one hand the Union Flag, and in the other, a naked sword. Beneath his feet are British flags, and a broken spear, shield and chain. Hovering by his side is the eagle, our national emblem, from whose talon the lightning of destruction is flashing upon the British lion. Britannia, with the crown falling from her head, is hastening toward a boat to escape to a fleet, which denotes the departure of British power from our shores. Upon a cloud, on the right is an angel blowing a trumpet, from which flutters a loose scroll. Upon the scroll are the sentences: "Palam nuntiata libertatis A. D. 1776 Fodus sociale cum Gallia, An. D. 1778. Pax: libertas parta An. D. 1783." (Independence declared A. D. 1776. Treaty of Alliance with France declared, A. D. 1778. Peace: independence obtained A. D. 1783.)

The diploma also includes an impression of the Eagle and two circular medallions replicating L’Enfant's design for the silver medal, planned as a third emblem of membership but never struck in the eighteenth century.

L’Enfant returned to America in time to present the finished Eagles and copperplate for the diploma to the Society’s first general meeting, which was held in Philadelphia in May 1784. The engraved plate that L’Enfant delivered from France did not include the printed text. A committee was quickly assigned to compose the wording, which was approved by the delegates on May 17:

Be it known that ______ is a Member of the Society of the Cincinnati; instituted by the Officers of the American Army at the Period of its Dissolution, as well to commemorate the great Event which gave Independence to North America, as for the laudable Purpose of inculcating the Duty of laying down in Peace Arms assumed for public Defense, and of uniting in Acts of brotherly Affection and bonds of perpetual Friendship the Members constituting the same.

In Testimony whereof I, the President of the said Society, have hereunto set my Hand at in the State of this __ day of ______, in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and _____and in the ____Year of the Independence of the United States.

By order,

__________ ,Secretary. __________ ,President.

The job of adding the text to the French-engraved plate was given to Robert Scot (1744?-1823) of Philadelphia, who later became engraver to the United States Mint. Society accounts also record payment to a Thomas W. Collins for “writing” the text in an elegant hand so that it could be copied by the engraver. It was not until November 1784 that Scot completed his work and printed the first batch of one hundred diplomas on parchment.

The printed blank diplomas were, as a rule, signed by George Washington and Henry Knox (as president and secretary) and then delivered to the constituent society secretaries to be inscribed to the individual members. The first group of blank diplomas was sent to Washington at Mount Vernon on January 24, 1785, by Gen. Otho Holland Williams, assistant secretary general, who requested that Washington sign them for members of the Pennsylvania Society. Washington’s prompt response is recorded in his diary entry for a snowy February 2, 1785: “Employed myself (there could be no stirring without) in signing 83 Diplomas for the members of the Society of the Cincinnati, and sent them to the care of Colo. Fitzgerald in Alexandria, to be forwarded to General Williams of Baltimore.”

Washington wrote to Williams the same day to let him know that the signed diplomas were on their way back to him. But neither Washington’s letter nor the diplomas ever reached their destination. In April, Williams learned from authorities in Baltimore that several blank Society diplomas bearing Washington’s signature had been found in the possession of an inmate of the city jail. An interview with the man led Williams to a desolate part of town where, he wrote, “I never saw a more abandoned set of Mortals of both Sexes collected together. After an hours fruitless search I went from thence to the Stage office but could not find any Letter receipt for the delivery.” Although pessimistic about ever recovering the rest of the diplomas, Williams was hopeful they would not be used for false purposes: “Those I found were much abused—dirty—rumpled, and bore no marks of forgery, and from the situation in which a wretched old Woman shewed me the others had been, it is impossible that they could be fit for the uses intended.”

This initial setback did not dissuade Washington from continuing to sign groups of diplomas for the individual constituent societies, although from then on the precious cargo was entrusted only to a representative of the Society. The Pennsylvania Society quickly regrouped with a request for signatures on 250 new diplomas, which were hand-delivered to Washington by the state society secretary, Richard Fullerton, on October 31, 1785. Maj. James Fairlie visited Mount Vernon for several days the following December, departing on the twelfth with 251 signed diplomas for the New York Society. Washington’s diaries and correspondence record subsequent signings for several other constituent societies, among them New Jersey (November 6, 1786), South Carolina (April 5, 1787), Delaware (April 27, 1787), Rhode Island (September 17, 1787), and France (August 7, 1790).

The name of the recipient of the diploma was generally filled in by the appropriate state secretary, and the surviving examples vary greatly in form and calligraphy. In September 1789, Secretary General George Turner instructed Nicholas Gilman of the New Hampshire Society on the form he preferred “[T]o preserve uniformity in filling up the diplomas (a business I must now leave to yourself) … I have hitherto inserted, with the name of the member, the rank which he bore at the end of the war; together with the corps to which he belonged. If an honorary member, we insert his name only, unless he fills, or has filled some honourable appointment in the state or U.States. This forms a necessary discrimination between the men of the sword, or members of right, and those who are admitted of grace.”

Two years earlier, however, the Virginia Society had passed a resolution that the “1st Blank” on the diploma would be inscribed with “the name of the member applying for the Diploma, and the words ‘Esquire of the Commonwealth of Virginia’,” without any reference to military service or rank.

The dating of the diplomas also varied from state to state. In the same resolution, passed on April 24, 1787, the Virginia Society decreed that from thenceforth every diploma issued to a member of the Virginia Society would be inscribed with the place and date: Mount Vernon, Virginia, March 1, 1787. Similarly, the Pennsylvania and New York diplomas are marked uniformly with the date Washington signed, regardless of when they were issued to the members. Several surviving diplomas issued to members of the Rhode Island Society, on the other hand, bear the date January 1, 1784—predating L’Enfant’s arrival from France with the copperplate.

L’Enfant’s hope that a diploma would be given to every member was dashed by financial realities. To offset the costs of parchment, printing, and travel, most of the state societies charged their members a fee to acquire a diploma. The earliest subscribers from the Pennsylvania Society paid one dollar each, while New York members were assessed twenty-four shillings. In Massachusetts in 1794 the price for a diploma was reduced from four to two dollars, with an order to use the proceeds to refund the difference to any member who had paid the higher price.

Following Washington’s death in 1799, several of the constituent societies adopted their own membership certificates. While most closely resembled L’Enfant’s design, the text was altered to reflect the status of a successor member, the state society affiliation, and the change in the century. A surplus of original diplomas signed by Washington and Knox remained in the archives of several societies. New York Society records show that during the early part of the nineteenth century, some of the Washington and Knox-signed copies were still being issued to members. James Davidson, “late Commissary General Hospital Department,” who did not join the Society until 1811, paid the New York Society treasury five dollars for an original diploma in May 1812. Commodores Stephen Decatur and William Bainbridge, elected honorary New York Society members in 1813, were each issued one of the precious Washington and Knox-signed diplomas. The minutes of the New Jersey Society record that, in 1814, twenty-seven signed blank diplomas were deposited in the State Bank at Elizabeth; twenty-five of these remained in the “Treasurer's trunk” when an inventory was taken in 1826.

In a circular letter to the constituent society presidents dated October 31, 1786, Washington wrote that he would be “constantly ready to sign such Diplomas as may be requisite for the Members of your State Society, being sincerely desirous of giving every possible proof of attachment, esteem & affection for them.” The return of these sentiments by the membership is well demonstrated in the number of original diplomas that have survived, treasured by generations of descendants and collectors. In addition to L’Enfant’s original drawing of the design and the original copperplate from which the diplomas were printed, the Society’s library collection includes nearly fifty original diplomas bearing Washington’s signature.

The library maintains a census of diplomas in other institutional and private collections. Anyone with information about existing Society of the Cincinnati diplomas is encouraged to contact the library staff at library@societyofthecincinnati.org.

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant

June 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

At the request of the Society, Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, a French volunteer in the Continental Army Corps of Engineers, drew an ink-and-wash design for a medal bearing imagery of the life of the fifth-century BC Roman hero Cincinnatus, from whom the Society took its name. The obverse, shown here, depicts Cincinnatus receiving his sword from Roman senators as he leaves home to lead his country against its enemies.

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant

June 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

The reverse of L’Enfant’s design for the proposed medal depicts Cincinnatus returned to his plow following his victory in war. Although the Society adopted the medal as an emblem of membership, none was struck in the eighteenth century. Impressions of the medal’s obverse and reverse were incorporated into the design of the engraved plate for the diploma.

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant

June 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

This cutout of the design for a badge in the form of an eagle suspended by a blue-and-white ribbon was submitted by L’Enfant as an alternative to the medal described in the Institution. In June 1783, the Society adopted the Eagle as its official insignia. General Steuben, acting as president pro-tem of the Society, boldly signed his name across the top of the ribbon, consigning this original watercolor drawing to the archives. An engraved image of the Eagle appears at the top of the diploma.

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant

June 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

Concerned that all members of the Society might not be able to afford to purchase an Eagle, L’Enfant also submitted this design for an elegant membership certificate, to be called the diploma. The imagery depicts America forcing Britannia away from her shores, with Fame heralding the achievement of American independence. The Society adopted the diploma and the Eagle as the official emblems of membership at its June 19, 1783, meeting.

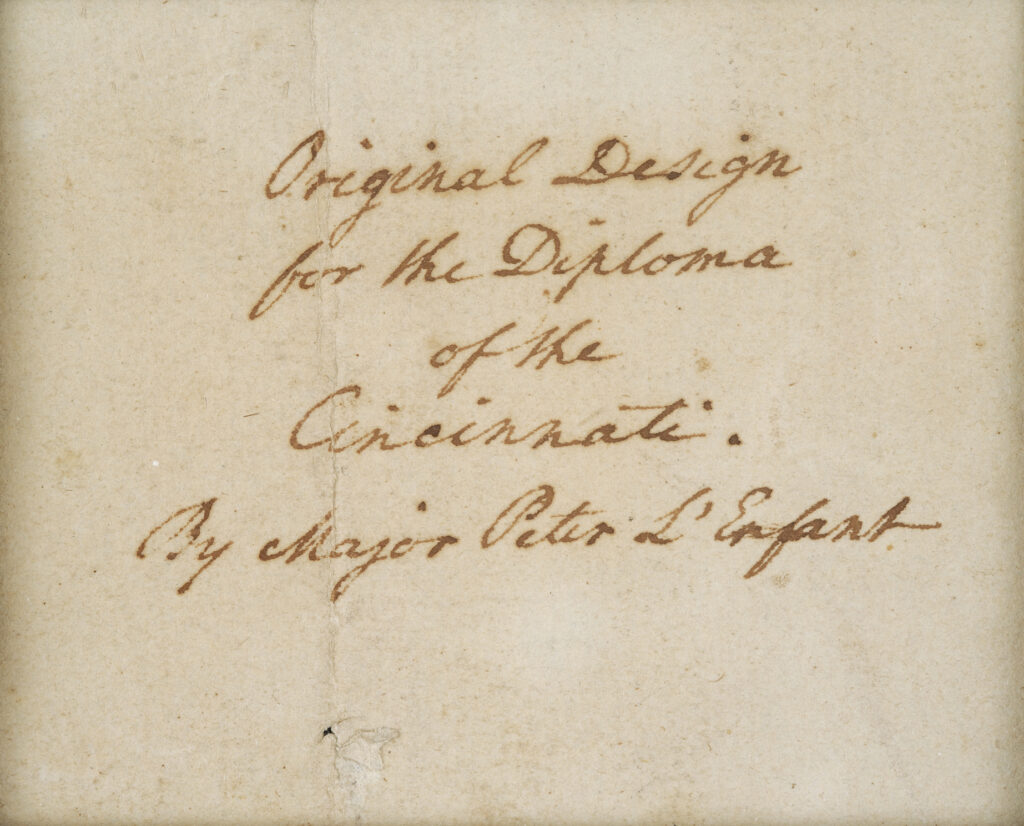

George Turner

ca. 1787

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

While serving as secretary general of the Society, George Turner of South Carolina annotated the back of L’Enfant’s drawing of the diploma: “Original Design for the Diploma of the Cincinnati By Major Peter L’Enfant,” using the anglicized version of the name by which L’Enfant was known in America.

George Washington

October 16, 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

In the fall of 1783, L’Enfant traveled to Paris to oversee the production of the first gold Eagles and the engraving of a copperplate for the diploma. This certificate, signed by George Washington as president general, states that L’Enfant is a member of the Society and is authorized to “transact some necessary business relative to the Order” while in France.

Jean-Jacques Le Veau (after Augustin-Louis La Belle and Pierre-Charles L’Enfant) and

Robert Scot

1784

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

While in France, L’Enfant arranged to have a copperplate made for printing the diploma, based on his original design. The French artist La Belle and engraver Le Veau captured L’Enfant’s powerful imagery, but left the center blank. The text of the diploma was added by Philadelphia engraver Robert Scot after L’Enfant returned to America.

Signed by George Washington and Henry Knox

September 1, 1789

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mrs. Edward Correa, 1955

The Society diplomas were printed on parchment and issued to the constituent societies for distribution. The officers of the constituent societies then arranged to have the diplomas signed en masse by both George Washington as president and Henry Knox as secretary, before they were inscribed to the individual members. This diploma was issued to Lt. Matthew Gregory, an officer of the Connecticut Line who served with distinction at the Battle of Yorktown.

Chinese

ca. 1786-1790

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Lucille S. Pfeffer, 1984

This Chinese-export punch bowl was made for Ebenezer Stevens, an original member of the New York State Society of the Cincinnati. Its design incorporates the imagery and text of Steven’s printed diploma around the exterior of the bowl. In this view, the armored figure representing America confronts Britannia. The silver-gilt mounts on the rim and foot of the bowl are believed to have been added in the early nineteenth century.

Chinese

ca. 1786-1790

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Lucille S. Pfeffer, 1984

This view of the Ebenezer Stevens punch bowl shows the full text of his diploma, complete with his name inscribed and the signatures of George Washington and Henry Knox. A polychrome punch bowl with similar imagery was made for Richard Varick, another original member of the New York branch of the Society of the Cincinnati. It survives in the collection of Morristown National Historical Park.

H. Siddons Mowbray

1909

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Isabel Anderson, 1938

This detail of an oil-on-canvas mural decorating the Key Room on the second floor of Anderson House shows George Washington presenting the diploma of the Society of the Cincinnati to the marquis de Lafayette. Commissioned by Larz Anderson, a hereditary member of the Society, it is part of a series of wall panels that highlight momentous events in American history in which members of the Anderson family took part.