Viewed by many as a second war for independence, the War of 1812 tested the new American nation’s sovereignty, identity, and military just thirty years after its Revolution. The United States declared war against the British after suffering nearly a decade of abuses on the high seas as a result of the Napoleonic Wars between Great Britain and France. With the battle cry “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights,” the United States fought largely because of the impressments of its sailors, violation of its neutrality rights, and restriction of its foreign trade.

The War of 1812 was a divisive and unpopular conflict in some quarters of the country, but many of its supporters were veterans of the Revolution and invoked the need to preserve the nation’s hard-won independence when defending this new war. In an Independence Day address less than one month after the start of the war, Ebenezer Elmer, a veteran of Washington’s army and adjutant general of the New Jersey militia in the War of 1812, argued that America had been driven to “the last resort—the resort to arms; we are now called upon by the constituted authority of our country to defend that independence and those privileges with our arms which we obtained by them.”

Although the war ultimately ended in a stalemate, the American public believed their side had won. Victories at sea against a superior British navy and dramatic successes at Baltimore and New Orleans created a new generation of military heroes. Many of these men were members of the Society of the Cincinnati—whether aging veterans of the Revolution, sons and nephews of original Society members, or others newly elected to honorary Society membership for their valor. This renewed sense of national pride coincided with an increase in American manufacturing, resulting in an explosion of goods made to commemorate these men. Congress and state and city governments presented their heroes with swords, medals, and silver and commissioned paintings in their honor. For ordinary Americans, ceramics, textiles, prints, books, and songs brought the likenesses and stories of War of 1812 heroes into their homes. For many of the heroes themselves, membership in the Society of the Cincinnati—and the right to wear its venerable gold Eagle insignia—communicated to their contemporaries and to later generations of Americans that these officers wished to be remembered as defenders of the American independence that George Washington and his troops had secured.

Ezra Ames (1768-1836)

ca. 1815

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Robert Gardiner, Robert Copeland Jones, Alexander Hamilton Rice, and Henry Benning Spencer, 1955

Dozens of members of the Society of the Cincinnati who served in the War of 1812 had their portraits painted wearing their Society Eagle insignia on their uniform. Thomas Humphrey Cushing, an original member of the Massachusetts Society, capped a thirty-year military career as a brigadier general during the War of 1812 and commissioned Ezra Ames to paint this oil portrait wearing a Society Eagle on his War of 1812 uniform.

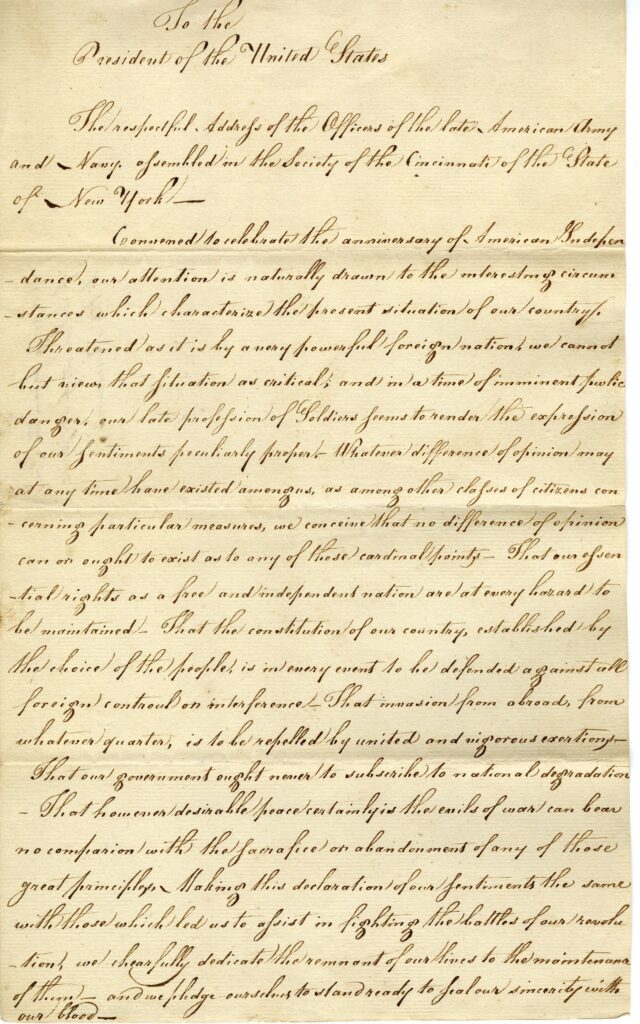

ca. 1812

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Members of the New York Society—veterans of the Revolution whose “late profession of Soldiers seems to render the expression of our sentiments peculiarly proper”—declared their support for a second war with Great Britain in this address to President James Madison. “Making this declaration of our sentiments the same with those which led us to assist in fighting the battle of our revolution, we cheerfully dedicate the remnant of our lives to the maintenance of them—and we pledge ourselves to stand ready to seal our sincerity with our blood.”

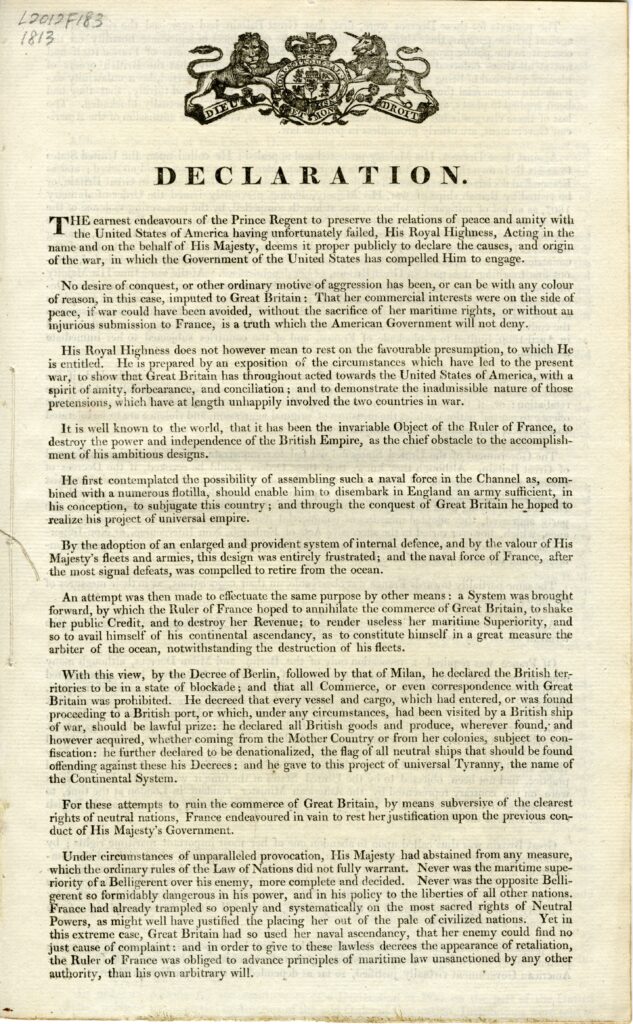

Westminster: Printed by R. G. Clarke, 1813

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The United States declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. After more than six months of fighting in Canada and along the Great Lakes, the British Crown announced that it was officially at war with the United States in this declaration issued on January 9, 1813.

Benjamin Tanner, engraver, after Hugh Reinagle, artist

Philadelphia: B. Tanner, 1816

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Walter P. Swain Jr. Memorial Collection, Gift of Philip S. Keeler, Jr., 1998

America’s earliest and most heralded victories of the war came at sea. One of the last took place on September 11, 1814, on Lake Champlain, where a small naval force under Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough, an honorary member of the New York Society, defeated a British squadron and repelled the enemy’s final attempt to invade New York.

U.S. Mint, Philadelphia, after designs by Moritz Fürst

ca. 1820

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of W. B. Shubrick Clymer, Society of the Cincinnati of the State of South Carolina, 1969

Congress bestowed gold and silver medals on dozens of War of 1812 heroes. In 1816, Congress awarded a gold medal to Charles Stewart, commander of the USS Constitution and an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Society, honoring his victory over the HMS Levant and Cyane in February 1815. Congress also issued silver medals to Stewart’s commissioned officers in the battle, including this one awarded to Lt. William Branford Shubrick, a hereditary member of the South Carolina Society.

Fletcher & Gardiner, Philadelphia

1813

Collection of Hull P. Fulweiler

Commissioned by Philadelphia merchants for American naval hero Isaac Hull, this silver urn honors the United States’ first naval victory of the War of 1812, when the USS Constitution, commanded by Captain Hull, captured the HMS Guerrière in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in August 1812. Taller, heavier, and more ambitious than any other piece of silver previously made in America, the Hull urn bears a scene of the battle on one side and an inscription on the other, surmounted by an American eagle clutching a thunderbolt.

Stephen Richards, New York, N.Y.

ca. 1813

Collection of Hull P. Fulweiler

“In testimony of the high Sense which it entertains of the patriotism and ability” of Isaac Hull and his victory over the HMS Guerrière, the New York branch of the Society elected him an honorary member on February 6, 1813. As part of his installation as a member—which did not take place for almost two years due to Hull’s military duties—he received this gold-and-enamel Eagle, which the New York Society commissioned from jeweler Stephen Richards for $30.

Richard Burlin (fl. 1843-1860)

1840

The Society of the Cincinnati, Anonymous gift, 1970

Major General Morgan Lewis, an original member of the New York Society, served as quartermaster general of the United States Army and held a field command during the War of 1812. He oversaw the capture of Fort George, Ontario, and commanded at Sackets Harbor, New York. While serving as the Society of the Cincinnati’s president general, he commissioned this oil portrait of himself wearing the Diamond Eagle insignia.

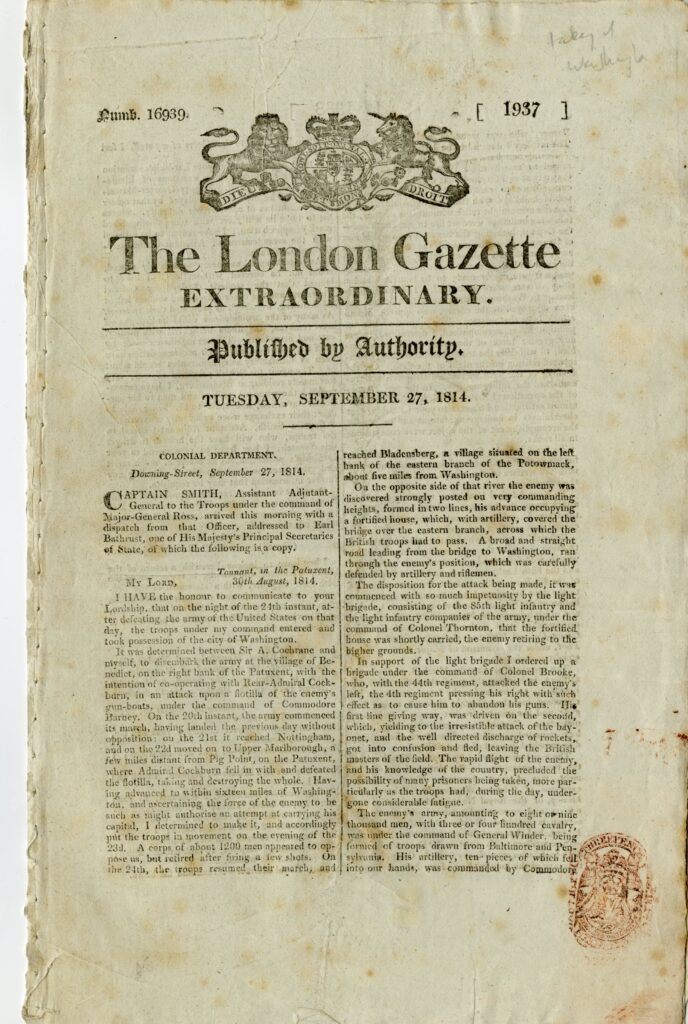

September 27, 1814

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

In August 1814, a disastrous American defeat at Bladensburg, Maryland, allowed the British to capture Washington and burn its public buildings. The reports of the British commanders printed in the London Gazette celebrated their triumph.

ca. 1814-1815

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of William Joshua Barney, Jr., Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1990

In honor of his spirited but failed attempt to prevent the British from overrunning the American capital, Joshua Barney received this presentation sword from the City of Washington. The sword was embellished with gold damask decorations on the blued steel blade representing naval figures and trophies, an eagle head pommel and eagle within a shell-shaped shield on the hilt, and additional decorations on the silvered bronze scabbard.

Nicolas Jean Francastel and Claude Jean Autran Duval, Paris, France

January 1784

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of William Joshua Barney, Jr., Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1990

Joshua Barney, a veteran of the Revolution, was an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati. He sat for at least two portraits wearing this gold-and-enamel Society Eagle insignia on his naval uniform.

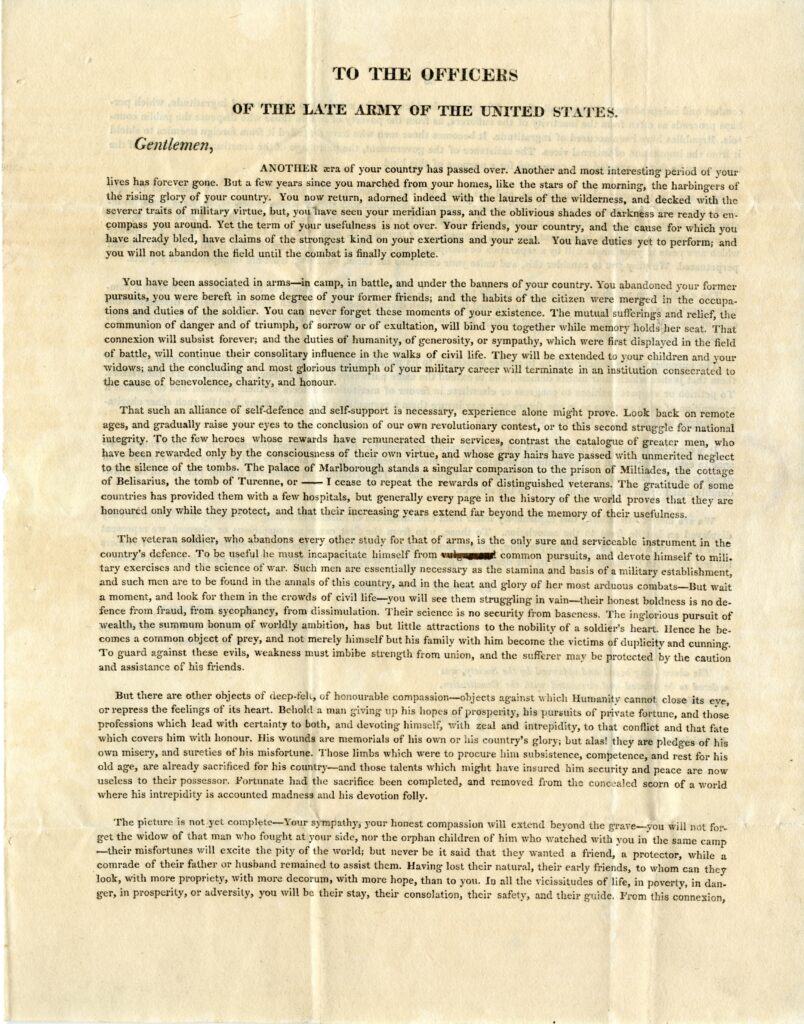

Philadelphia, June 15, 1815

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Shortly after the War of 1812, veteran officers circulated this broadside to propose establishing the Belisarian Association to maintain the soldiers’ bonds, help support veterans of the war and their families, and encourage recognition of the veterans’ sacrifices and achievements—strikingly similar purposes to those of the Society of the Cincinnati. It is unknown if the association, named after the ancient Roman general Flavius Belisarius, was ever formally organized.

Samuel Lovett Waldo (1783-1861)

1813

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Colvin C. Lombard, 1970

Col. Jacob Kingsbury, an original member of the Connecticut Society, commanded Fort Detroit on the eve of the War of 1812 before being transferred east to the Second Military District. He wears his Society Eagle insignia in this portrait painted during the War of 1812.

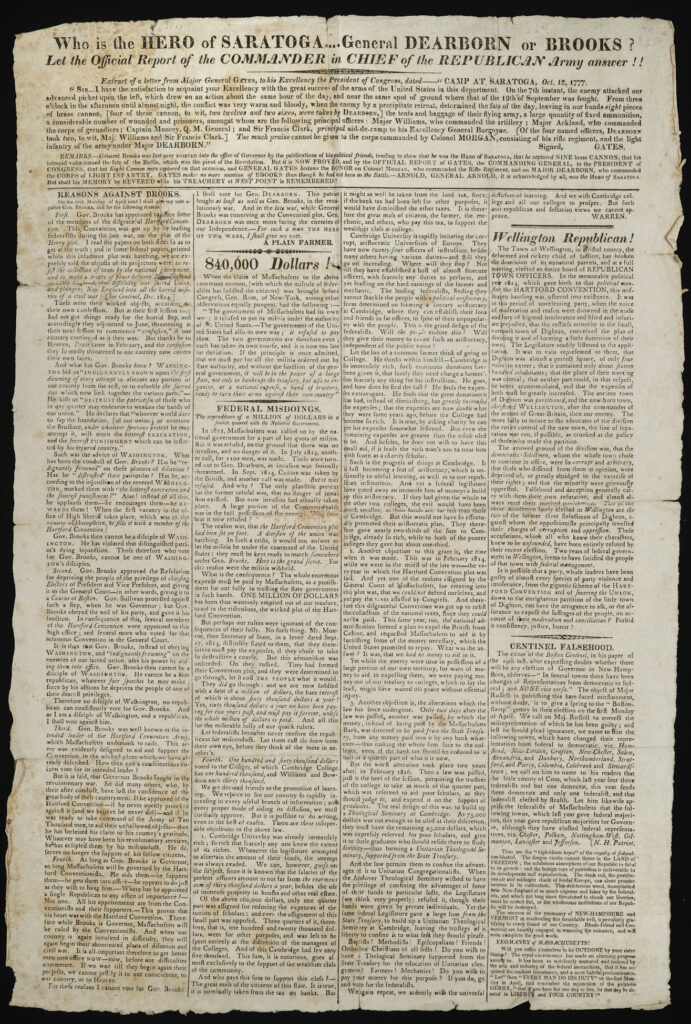

[Boston: Printed by Adams and Rhoades, 1817]

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

The importance of an officer’s service in the War of 1812 lingered in peacetime. This politically charged broadside from the Massachusetts governor’s race in 1817 argued for Henry Dearborn over the incumbent John Brooks—both original Society members—because Dearborn served in the War of 1812 while Brooks opposed it. The author also cited the candidates’ Revolutionary War service as ammunition, claiming that Dearborn was “the Hero of Saratoga.”