Cincinnatus on Downing Street: Winston Churchill Joins the Society

This article is adapted from “Cincinnatus on Downing Street: Winston Churchill Joins the Society” by Ellen McCallister Clark, published in Cincinnati Fourteen 47, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 10-15.

Watch the Fox Movietone newsreel of a portion of Churchill's visit to Anderson House in January 1952.

Members of the Society of the Cincinnati enjoy pointing out that the great British statesman Sir Winston Churchill was admitted as a hereditary (not honorary) member of the Society. And it is evident from Churchill’s remarks and writings that he too quite enjoyed this fact. Elected to membership in the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut in 1947, he often noted his Society connection when speaking to American audiences. In a 1950 Fourth of July speech to the American Society in London, for example, Churchill remarked, “Among Englishmen, I have a special qualification for such an occasion. I am directly descended through my mother from an officer who served in Washington’s Army. And as such I have been made a member of your strictly selected Society of the Cincinnati.”

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was born at Blenheim Palace on November 30, 1874. His father was Lord Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill (1849-1895), a descendant of John Churchill, the first duke of Marlborough who was Queen Anne’s commander during the War of Spanish Succession. Winston’s mother was Jeanette (called Jennie) Jerome of Brooklyn, who was the daughter of Leonard Jerome, a New York financier and sometime editor of the New York Times, and his wife, the former Clara Hall.

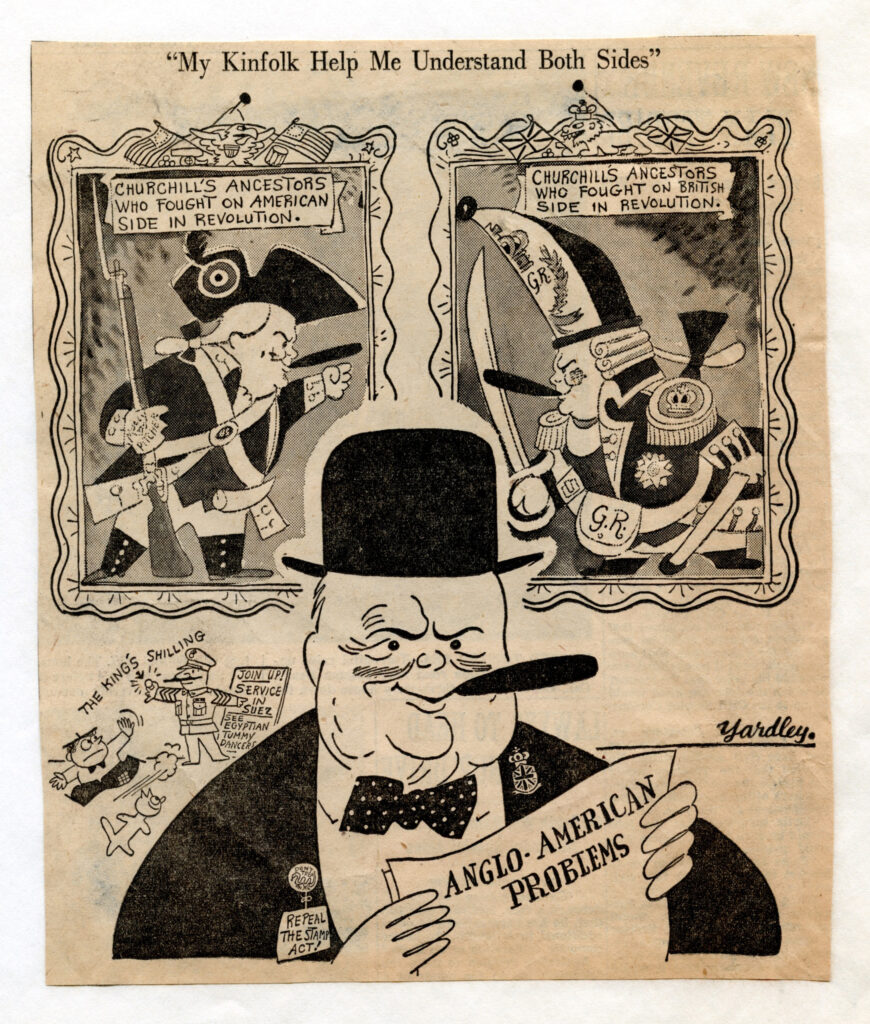

At least four of Churchill’s direct maternal ancestors fought on the American side during the War of Independence: Two of his ancestors, Samuel Jerome and Ambrose Hall, served in the Berkshire County (Mass.) militia; another great grandfather was Maj. Lebbeus Ball of the Fourth Massachusetts Continental Regiment; and a great-great grandfather through the Jerome side, Lt. Reuben Murray, served in the Connecticut Line and in the Connecticut and New York militias. According to his grandson and namesake, who edited a selection of Churchill’s writings on America, Churchill had no ancestors who fought on the British side during the conflict he famously described as the “War between Us and We.”

Churchill was clearly proud of his American ancestry, and he made the most of it in cementing the “Special Relationship” between Great Britain and the United States during his terms as prime minister. Both he and President Franklin Roosevelt took pleasure in noting the fact that they were distant cousins. In his first address to a joint session of the U. S. Congress in 1941, Churchill quipped: “Had my father been American and my mother British, instead of the other way ‘round, I might have got here on my own!” And that same year, when accepting an honorary degree from the University of Rochester, he brought up his Revolutionary War roots, saying, “I expect I was on both sides then, and I must say I feel on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean now.”

So it is not surprising that the Society of the Cincinnati, in the glow of the allied victory of World War II, sought out Churchill for membership. The invitation came in the form of a letter, dated April 12, 1947, from Col. Bryce Metcalf, who was then both president of the Connecticut Society and president general:

Sir,

Permit me to write to you of The Society of the Cincinnati, founded by General George Washington and his fellow officers of the Continental Army in 1783, an hereditary order that still flourishes ….

It is a source of great satisfaction to report to you that the Society holds you to be eligible to hereditary membership in the right of your ancestor, Lieutenant Reuben Murray of Burrall’s Regiment, such membership being in the Society in the State of Connecticut, where Lt. Murray received his Continental commission.

Colonel Metcalf continued with details about membership and then closed with: "I should like to add that I am also President General of the entire Society and take especial pride in assuring you of the general gratification which will be felt throughout the order if you consent to be the first Englishman ever to be elected an hereditary member."

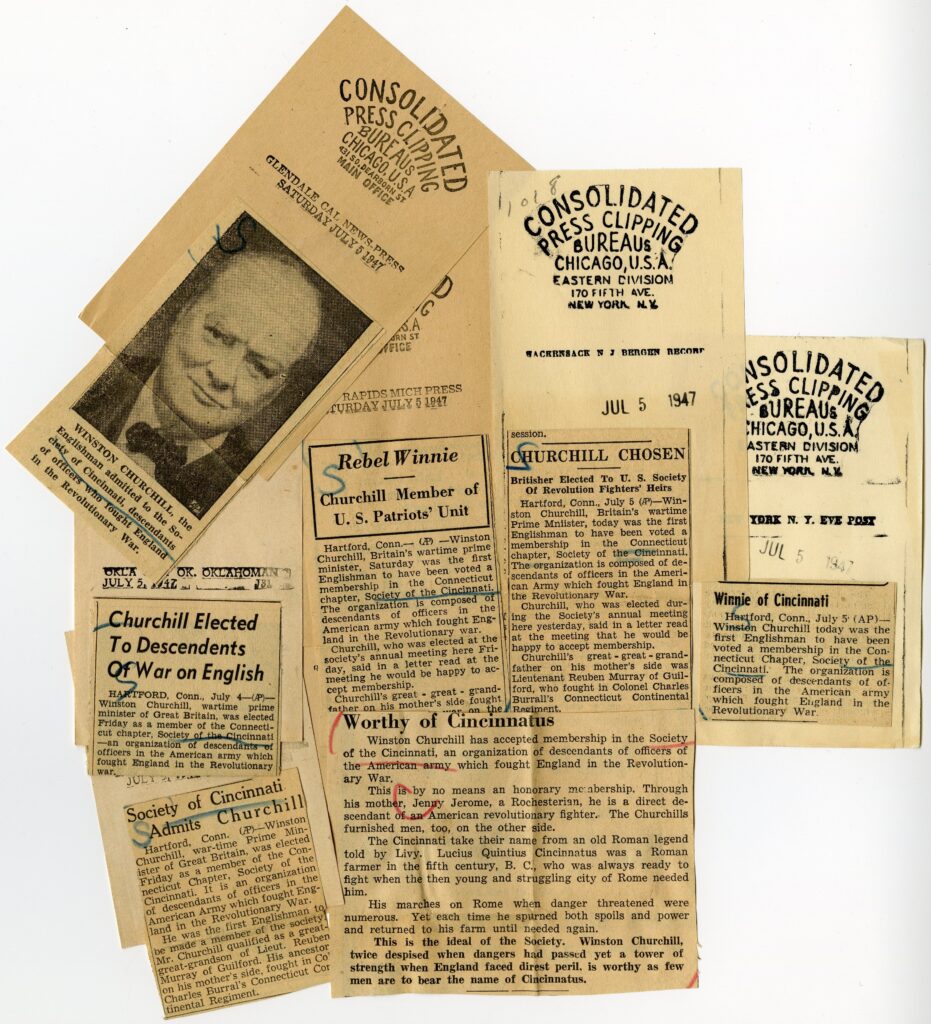

Churchill did indeed accept membership in the Connecticut Society in 1947, which made the news around the country. The Society library has a packet of newspaper clippings of the coverage, whose headlines range from approving (“Worthy of Cincinnatus” in the Olean (N.Y.) Times Herald) to bemused (“Rebel Winnie” in the Grand Rapids (Mich.) Press).

It was not until almost five years later that opportunity arose for Churchill to meet with the Society and receive its emblems of membership—the Eagle and the diploma. Unfortunately, Colonel Metcalf, his fellow Connecticut Society member, did not live to witness this great occasion. Bryce Metcalf died in October 1951, and in November of that year, another stalwart of the Society, Gen. Edgar Erskine Hume, was elected president general. It fell to Hume to seize the moment, with Churchill’s announced visit to meet with President Truman in January 1952, to invite him to Anderson House. On January 7, 1952, General Hume wrote to Churchill:

My dear Mr. Prime Minister:

Arrangements have been made, with your approval, for the presentation to you of the Eagle and Diploma of hereditary membership in the Society of the Cincinnati. The ceremony will take place at Anderson House, 2118 Massachusetts Avenue, Headquarters of the Cincinnati, on 16 January 1952 at 5 o’clock.

Your fellow members of this old Society feel that there can be no more appropriate way to demonstrate the common ideals which unite the British and American peoples than by investing Britain’s first Minister with the badge of a military order of which General Washington was the first President General. Throughout the 169 years of the existence of the Society of the Cincinnati the example of Cincinnatus of old has been revered. Washington, whom Lord Byron called the Cincinnatus of the West, left all to serve the Republic, and thus our order derives its motto. You too, Mr. Prime Minister, have demonstrated to mankind your own willingness and that of the gallant Nation that you lead, to sacrifice all for principle. Your name will illuminate our rolls with undying brightness beside other great men who have been members of this body.

The Sir Winston Churchill Archives held at the University of Cambridge include a detailed memo written by the prime minister’s press secretary about the arrangements for the Anderson House visit. The whole event was supposed to take place in less than an hour. After the presentation of the Eagle and Churchill’s brief remarks in the Ballroom, the prime minister and General Hume were to retire to the adjacent Great Stair Hall for official photographs. There were 140 people in attendance, including Vice President of the United States Alben Barkley and the Chief Justice of the United States Frederick Moore Vinson, who was himself an honorary member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia. In addition to other officials from the U.S. government and the British Embassy, leaders of the Society of the Cincinnati were invited. Because of space limitations, no spouses were included, which (this being 1952) made it an all-male affair. After photographs, Prime Minister Churchill and General Hume rejoined the assembled guests for refreshments of “champagne and whiskey.”

The press secretary’s memo noted:

The hall in which the ceremony is to be held is perfectly adapted for publicity. There is a lofty gallery at the far end of the hall…. There is room in the gallery for reporters, news reel cameras and television cameras. The Information Service is considering whether it would be desirable to have all these present. Their only doubt is about television, because there will be a great deal of this on the following day when the Prime Minister addresses Congress and it might be better, in this particular medium, to do nothing which could detract attention from the more important of the two occasions.

Right: Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President General Edgar Erskine Hume posed for this photograph after the formal presentation of the Eagle at Anderson House on January 16, 1952. (The Society of the Cincinnati Archives)

The Anderson House event apparently did not make the evening’s television news—but cameramen from Fox Movietone News were there. The segment showing Churchill receiving his Eagle was never actually used in the movie theater newsreels of Churchill’s 1952 visit to America, but a brief bit of footage, literally taken from the cutting room floor, was sent to the Society and is preserved in the library collections. In the one-minute, nineteen-second clip, Churchill is seen first seated in the center of a small platform erected in front of the fireplace in the Ballroom at Anderson House. On a table immediately before him, next to the microphones for audio recording, lie his signed diploma of the Society of the Cincinnati—printed from the original copperplate designed by Pierre L'Enfant in 1783. With the banner of the Cincinnati behind him, the prime minister stands while General Hume places a Society Eagle suspended from a ribbon around his neck. Churchill then delivered a short speech, a full transcript of which can be found in the Society’s archives along with Hume's opening discourse. Though the newsreel footage only includes Churchill's closing remarks, his final words of gratitude reverberate with characteristic intonation and spirit: "I thank you from the bottom of my heart for the kindness which you have shown me. I value this honor and let it be a help to all of those forces – they are, in my opinion, irresistible forces – which draw our two nations together; not for any unworthy purpose of combination or gathering strength, but in order that we may defend the freedom of the world."

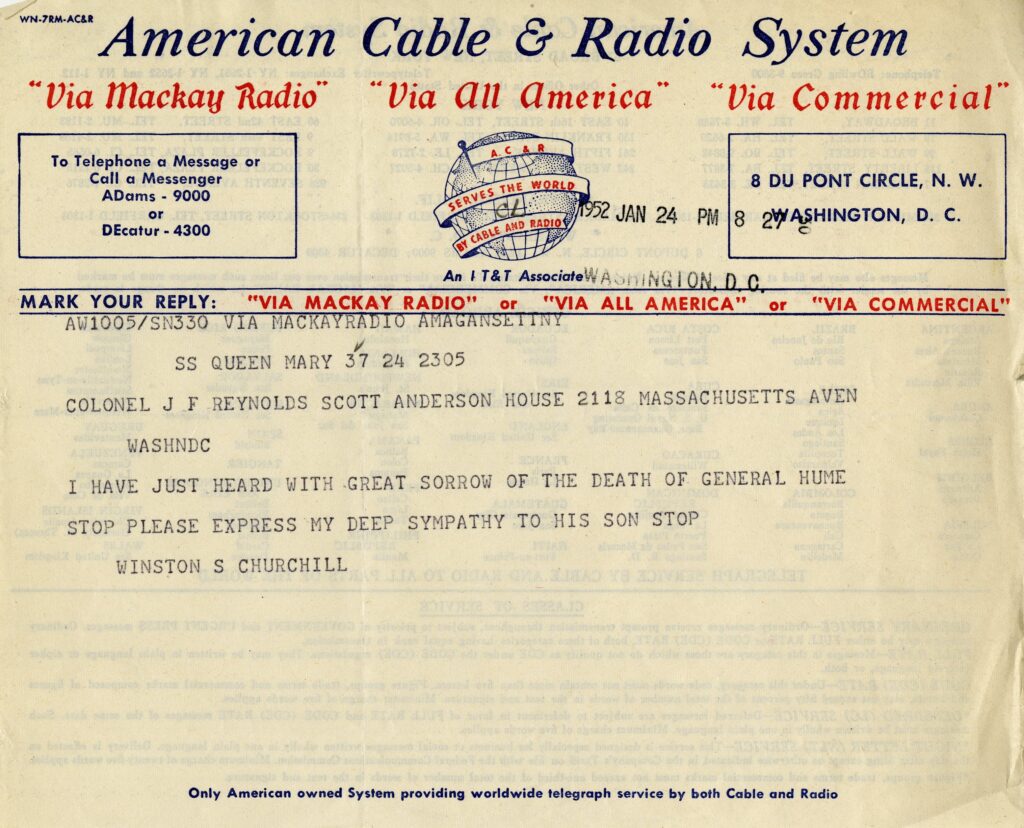

The presentation of Churchill’s Eagle capped Edgar Erskine Hume’s long and distinguished service to the Society of the Cincinnati. Aphysician and military officer who served in both World Wars, he was also the author of more than fifty books, many of them about aspects of the history of the Society. He was a devoted member of the Virginia Society, and for more than twenty years held offices in his state and with the General Society. Presiding over Churchill’s visit was Hume’s first major act upon assuming the office of president general, and sadly, it proved to be his last. He died suddenly, at Anderson House, eight days later on January 24, 1952.

Churchill, who was seventy-seven at the time of the presentation, lived on for more than a decade. Although he never again met with the Society, he remained a hereditary member in good standing, and his papers confirm that he retained an interest in the Society’s activities. In 1963, when a call went out for members to send copies of books they had written to establish the “Member Author” collection, Churchill sent an autographed copy of his biography of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, which is now preserved in the library’s holdings.

Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill died on January 24, 1965—thirteen years to the day after General Hume. After his death, the Connecticut Society realized that Lt. Reuben Murray’s length of Continental service was not long enough to technically qualify as an eligible line for membership, and they quietly changed Churchill’s membership status from hereditary to honorary.

In 2011, the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati announced that it admitted one of Churchill’s grandsons to membership in the right of another of his Revolutionary War patriot ancestors, Major Lebbeus Ball, thus reviving this special Anglo-American relationship.