"A Plea for a House": The First Campaign for a Society Headquarters

This article is adapted from “A Plea for a House — The First Campaign for a Society Headquarters" by Valerie Sallis published in Cincinnati Fourteen 49, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 32-39.

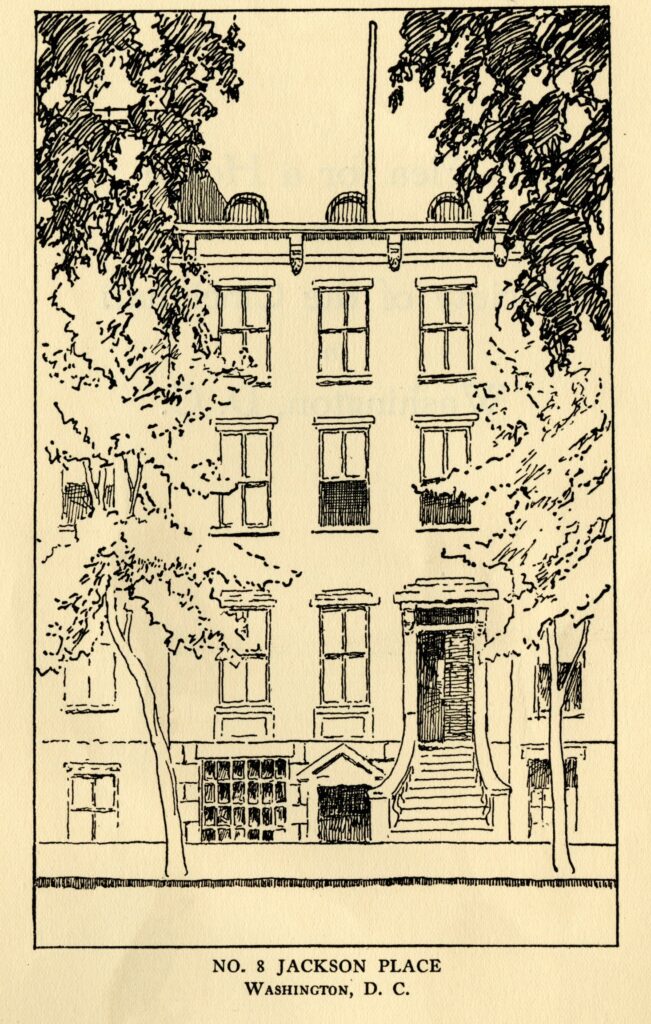

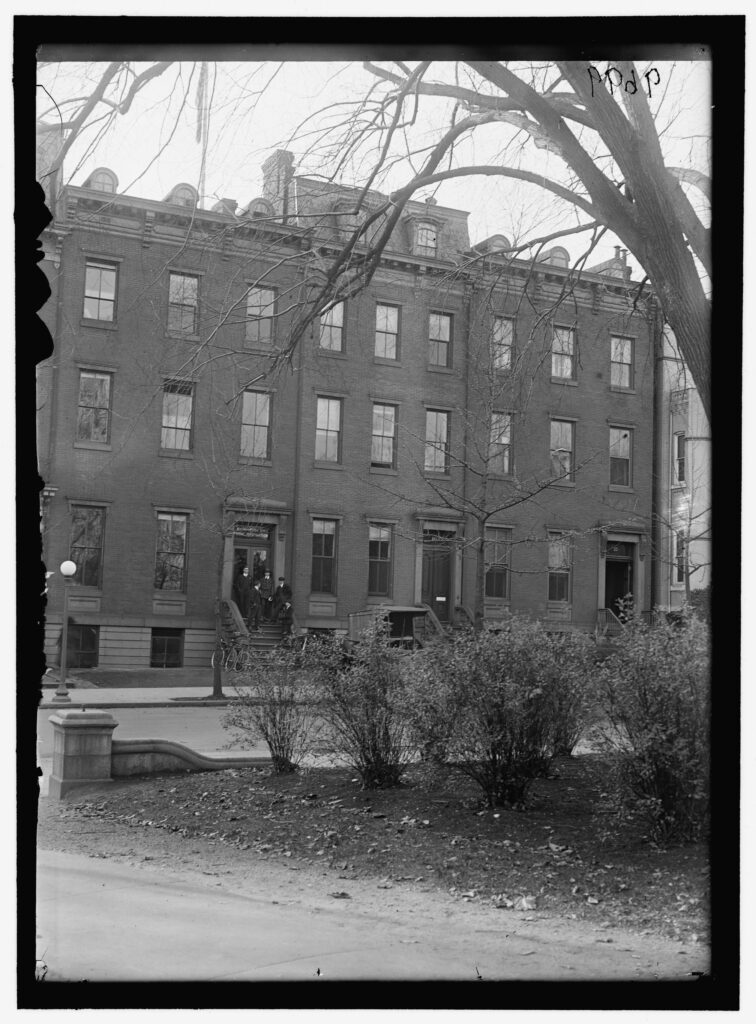

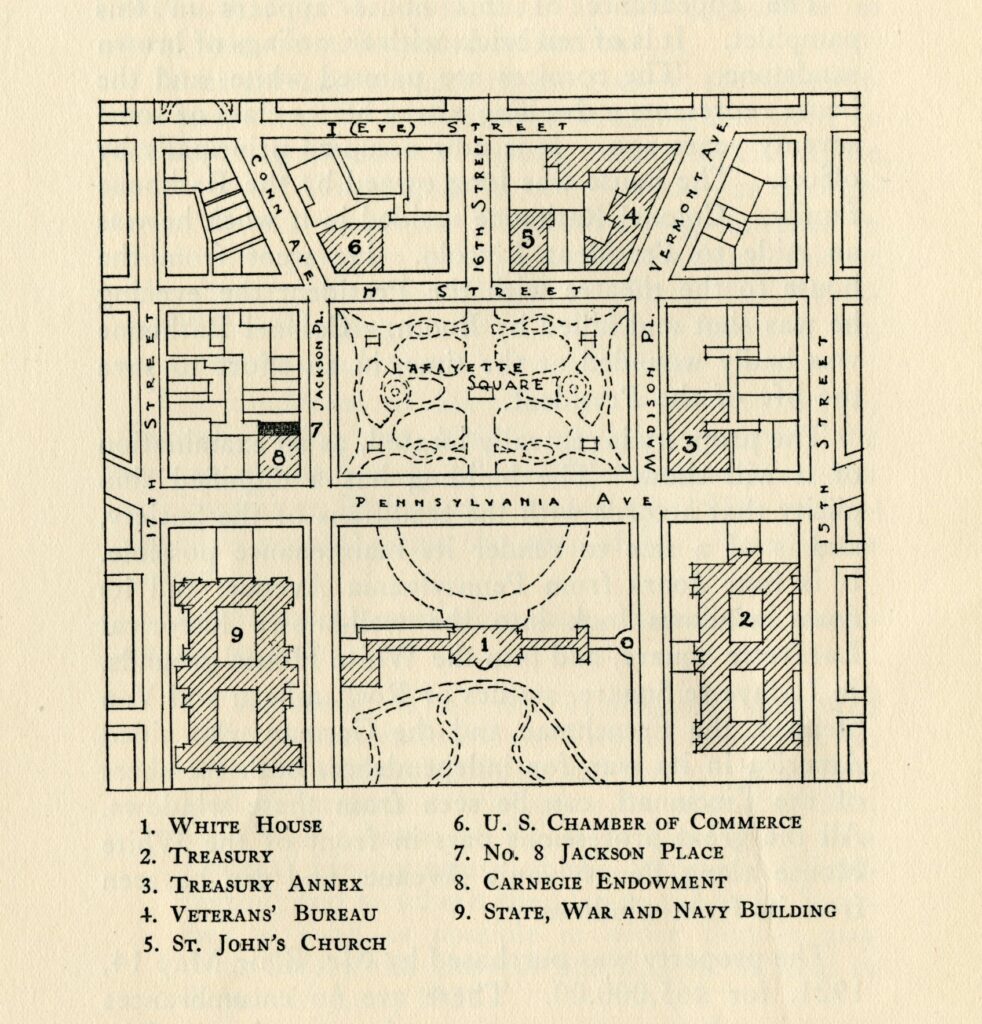

On the edge of Lafayette Square, little more than a stone’s throw from the White House, sits a small leafy street called Jackson Place—the Society of the Cincinnati’s road not taken. Almost a decade before the gift of Anderson House, a modest red brick row house at Number 8 Jackson Place was the object of an unsuccessful campaign to create a permanent headquarters for the Society. Despite its ultimate end, the tale of this house and the campaign is an interesting vignette from an overlooked period of the Society’s history.

The house on Jackson Place has an intriguing history. The property was purchased in 1858 by Commander James Alden, Jr.[1] After commanding ships under Admiral David Farragut during the Civil War, Alden was promoted to commodore in 1866 and spent several years serving on the Pacific coast. In April 1869, he was appointed the U.S. Navy’s chief of the bureau of navigation. Returning to Washington, Alden took up residence at the fashionable new Arlington Hotel and sold the house on Jackson Place in June 1869 to Clara H. Rathbone, the wife of Col. Henry R. Rathbone.[2]

Four years earlier, while still engaged to be married, the young pair came to national attention for sharing President Abraham Lincoln’s box on what would be his last visit to Ford’s Theater. Henry was stabbed in the shoulder struggling to stop John Wilkes Booth after Booth shot President Lincoln, and Clara remained by Mrs. Lincoln’s side keeping vigil near the wounded president. The tragedy haunted Rathbone and seems to have contributed to mental instability. While serving as U.S. consul in Germany in 1883, Henry killed Clara in a fit of insanity and died in an asylum for the criminally insane in Hildesheim, Germany, in 1911.

In the years following Rathbone’s death, as the commercial heart of Washington expanded rapidly—and families seeking a home were perhaps reluctant to choose a residence with such tragic associations—the house on Jackson Place was rented as office space. During World War I it was the headquarters of the Committee on Public Information—the propaganda arm of the federal government charged with encouraging volunteer enlistment. After the war, Gist Blair, a member of the Society of the Cincinnati who lived just around the corner on Pennsylvania Avenue, purchased Number 8 for $65,000.

8 Jackson Place was just a few hundred feet from the White House. In the 1920s Gist Blair and other members wanted it to become a patriotic center in a world capital.

The Blair family had been firmly established in Washington’s elite circles for over a century. Montgomery Blair, Gist’s father, was postmaster general during Lincoln’s administration and oversaw major reforms of the postal system. His grandfather, Francis Preston Blair, was editor of the Washington Globe and a part of Andrew Jackson’s unofficial “Kitchen Cabinet” of advisors. The family cherished their history in the city, and Lafayette Square in particular. In 1902, Gist and his siblings led the fight against the initial McMillan Plan designs that would have destroyed the residences around the square to make way for the construction of a sprawling new federal office complex.

Gist Blair had been a member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia since 1910. He was an active participant in Society affairs in the early twentieth century, along with fellow Virginia Cincinnati Col. John R. M. Taylor and Maj. John Clark McGuire. Blair and Taylor were residents of Washington, D.C., and had ample opportunity to observe as grand headquarters buildings were erected or purchased by other hereditary and fraternal organizations. The Daughters of the American Revolution’s massive and elaborate Memorial Continental Hall, in particular, captured their attention. They were struck by the fact that, though the Society of the Cincinnati was by far the oldest patriotic organization in the country, it had no official headquarters.

Blair, Taylor, and McGuire introduced the need for a headquarters as a topic of conversation at several Society dinners in the mid-1920s. By October 1927, the trio had generated so many responses favorable to the establishment of a headquarters that they were appointed at the fall meeting of the Virginia Society to constitute a committee charged with the selection and recommendation of an appropriate building. After searching the city for a suitable property with no luck—the committee was initially interested in finding a location in Georgetown—Blair offered the house at No. 8 Jackson Place as a solution.

In 1929, a pamphlet titled A Plea for a House for the Society of the Cincinnati in Washington, D.C. was distributed to members as a mass fundraising appeal for the purchase of Number 8 Jackson Place. The case for acquiring a headquarters contrasted the Society’s strange lack of a home with the DAR’s Memorial Continental Hall, the Sons of the Revolution’s purchase of Fraunces Tavern in New York, and the Colonial Dames’ recent acquisition of Dumbarton House in Washington. The Society was a rapidly growing organization in the 1920s—membership had almost doubled since the turn of the century and, for the first time in over 125 years, all of the original fourteen constituent societies were again active following the revival of the French Society in 1925. The establishment of a headquarters was promoted as a way for the Society to manage and encourage further growth.

The authors presented Washington, D.C.—centrally located and accessible to both American and French members—as the ideal location for a Society headquarters. It would serve as a patriotic center in a world capital. They also suggested that a national headquarters would provide a repository for the archives of the Society, where they could be returned from safe deposit in New York City and opened for research. With remarkable foresight they noted that the archives of the Society should not be a static collection. Rather, they should contain “accounts of the members of the Society since the Revolution up to the present time; they should prepare to include an account of members in the future.” Other proposed uses for the house included a grand location for Society members to host dinners and receptions. Considering the ways Anderson House is used today, the authors seem remarkably prescient in their suggestions.

The proposed purchase price for the house was $65,000—the same price Blair had paid in 1921. The authors set the ambitious goal of raising at least $150,000 more to provide sufficient funds for maintenance and pay salaries for a curator and archivist. The matter was to be taken up at the general meeting to be held in Boston in June 1929. Each state society was urged to collect pledges and raise support in advance.

Not all members were convinced by the plea. One opponent to the scheme was the president general himself. Winslow Warren wrote to Henry Randall Webb in May 1929 that “I am not in favor of the house at Washington. Cannot see how it would be used—even if the money could be raised.”[3] Warren abstained from voting on the resolution to buy Jackson Place at the Triennial Meeting—and was the only general officer who did not vote in its favor. Despite the active support of the vice president general and treasurer general, the resolution did not receive the necessary votes to pass. The vote was held on June 5, 1929, in King’s Chapel in Boston. Delegations from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia voted to ratify the resolution. Against it were Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Maryland, and, interestingly, Virginia—the state society of the three members who had made the selection. Following the vote, McGuire withdrew the offer to sell Number 8 on Blair’s behalf, as Gist Blair did not attend the Triennial Meeting.

Would the Society be different today had it purchased Number 8 Jackson Place? Would the more modest building and smaller space have limited the aspirations of future members? Or perhaps the proximity to the inner sanctums of government would have inspired even grander dreams? Would there have been space for a museum or library like those that exist today at Anderson House? Such what-if questions provide interesting opportunity for speculation—and though they are ultimately unanswerable, they are a reminder of the impact of today’s choices on tomorrow’s consequences. As the campaign pamphlet for No. 8 Jackson Place asserted, “The history of the Society did not end with the death of those who established it. Its history continued from 1783 and is being written every day.” In the end, it is not only the routes chosen that define that history, but also the roads not taken.

- Henry M. Rice to James Alden, April 7, 1858, Liber J.A.S. 152, fol. 352, Washington D.C. Land Records, DC Archives. ↩

- James Alden to Clara H. Rathbone, June 21, 1869, Liber D No. 9, fol. 344, Washington D.C. Land Records, DC Archives.; 1871 Washington City Directory microfilm, Washingtoniana Special Collections, District of Columbia Public Library. ↩

- Winslow Warren to H. Randall Webb, May 9, 1929, Archives of the Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, D.C. ↩