A Monument to George Washington in Philadelphia

This article is adapted from “‘Past and Present Share in Its Completion’: The Pennsylvania Society’s Monument to George Washington” by Valerie Sallis, published in Cincinnati Fourteen 50, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 16-29.

The creation of the magnificent monument to George Washington in Philadelphia is one of the great accomplishments of the Society of the Cincinnati. The dedication of the monument in 1897 was the culmination of a heroic effort by the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania that consumed nearly a century. It remains a monument, not just to George Washington, but also to the dedication of the Pennsylvania Society’s members to the task assigned them to perpetuate the memory of the American Revolution and its heroes.

The project began just a decade after George Washington’s death in 1799. The Society of the Cincinnati still counted among its members a number of men who had served under the general. Determined to create a monument while personal memories of Washington endured, the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania passed a resolution on July 4, 1810, “to establish a permanent memorial of their respect for the memory of the late father of his country, General George Washington, by the erection of a monument in the city of Philadelphia, has long been the wish of those who are desirous of perpetuating the recollection of his virtues.”

The Society appointed a committee consisting of David Lenox, William Jackson, Richard Peters, Charles Biddle, and Horace Binney, charged with fundraising. The group planned to raise the necessary funds by taking subscriptions from Society members, as well as from the citizens of Pennsylvania at large. The pace of the work was slow. The committee reported on July 2, 1811, that “so many occurrences have produced delay, that they have deemed it prudent to suspend commencing the necessary measures.”

The following year the Pennsylvania Society commissioned local bookbinder George Hyde to make 107 matching books for recording subscriptions. Each was bound in red leather with elaborate gilt tooling and contained an introduction about the plan to create a monument followed by blank pages for entering names and amounts pledged. The Society hired a courier to distribute the books to the Society members tasked with raising funds in the city wards and the surrounding counties. Each book was stamped on the cover with the name of the area in gold.

The subscriptions entered document the variety of donors to the project and the range of their financial circumstances. Members of the Pennsylvania Society led in pledging many of the largest sums. Horace Binney, secretary of the Pennsylvania Society, headed the list for Philadelphia’s Dock Ward with a contribution of $100. Born during the Revolutionary War, he was nineteen when Washington died. He had succeeded his father, Surgeon Barnabas Binney, as a member of the Pennsylvania Society in 1802. Binney later joined Lenox, Peters, and Biddle as a trustee for the monument fund and remained at the forefront of the monument movement for the next fifty years.

Leading citizens of the Philadelphia region were listed among the contributors. Elizabeth Chew and her son Benjamin Chew, Jr., made pledges of $40 and $30, respectively. The highest amount donated was $200 given by Charles Biddle’s son Nicholas who, while not a member of the Society, was the owner of a successful magazine and later a leading financier. Not all donors came from privileged backgrounds, and many of the entries in the subscription books were for contributions of one to five dollars.

Collecting the promised funds turned out to be a much more difficult matter than collecting pledges. On June 29, 1812, Jonathan Clark wrote to Charles Biddle that, “I have proceeded through York County with one of the books committed to my care, and am happy to inform you that our Farmers have subscribed the sum of three hundred and fifty dollars, but I cannot collect it until after the Harvest.” Clark’s difficulty in collecting was not unique. In the financial downturn following the War of 1812, many of the pledges were not made good at all or were not received for many years. By July 1815, the Society had only collected $2,132.74 of the pledged funds.

Tracking down the members assigned subscription books was itself an arduous task. An 1819 report of the Washington Monument Committee by Horace Binney stated that “it is impossible to say what is the precise amount of the subscriptions left unpaid, because the holders of the subscription books, in various parts of the state, not withstanding the most pressing solicitations have neglected to return them to the Trustees.” Of the 107 books commissioned, 23 remain in the Pennsylvania Society’s archives today—and several of these are completely blank.

Though correspondence on the subject by Binney and others continued, practical efforts in Philadelphia stalled for decades while monuments to Washington rose elsewhere. A renewal of interest was sparked by the marquis de Lafayette’s return to American in 1824, and a committee of citizens including some Cincinnati met at Merchant’s Coffee House, but no major gains were made. Dissatisfied with the progress, the one hundredth anniversary of Washington’s birth prompted another group of citizens to found their own Washington Monument Association at a meeting at Independence Hall. A design for a proposed monument was published and the cornerstone laid on February 22, 1833, in Washington Square. Having made a brave start, the new group also faced difficulties in raising enough to complete their monument.

Leaders of the Washington Monument Association wrote repeatedly to the Society over the next decade asking the members to transfer the Society’s larger fund to support their plan for the monument. But the Society’s trustees were wary of committing their money with no guarantee that the association could raise the funds needed to execute its plan. They preferred to wait and allow their funds to grow until the necessary amount was in hand. Without substantial funds, the proposed monument in Washington Square was never constructed, but its cornerstone remained in place—a reminder of the lapsed project for the next forty-five years.

Though the plans for a Society monument lay dormant, the Society’s fund continued to grow. Money trickled in from tardy subscriptions, and shrewd investment and mounting interest ensured the fund was anything but stagnant. A balance of $3,000 in 1825 grew to $137,500 by 1880. The Washington Monument Association’s smaller fund still existed but grew more slowly. It amounted to just $48,500 in 1880.

The Society did not forget the funds or the project. Officers of the Pennsylvania Society—William Wayne, George Washington Harris, and Richard Dale—were determined not to let the effort languish. In 1878, they formed a committee and sought designs from well-known sculptors in a contest to select a plan for the monument. Deciding to unite the separate efforts in order to bring a Washington monument to completion, the Society filed a legal petition to subsume the other fund and gained control of the Washington Monument Association’s contributions.

By February 1880, four designs had been submitted and reviewed by the Pennsylvania Society. The winning proposal was submitted by German sculptor Rudolf Siemering. Born in 1835 in Konigsberg, Germany, Siemering had studied at the Berlin Akademie under Gustav Bläser. Rudolf Siemering was already a leading monumental sculptor in his own country. His most famous work was an equestrian statue of Frederick the Great completed in Marienburg in 1877.

Siemering’s elaborate design for the monument incorporated an equestrian statue of Washington with myriad symbolic bronze figures. An enormous historical tableau on three levels, the Washington monument was to be constructed on a stepped granite base that measured sixty-one by seventy-four feet. A bronze statue of Washington topped the monument. The highest point, rising to forty-four feet above the ground, would be formed by Washington’s head. His horse was to rest on an oblong pedestal seventeen feet high with the inscription “Erected by the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania” carved around the top.

The remainder of the monument was devoted to layer upon layer of patriotic symbols. Bas reliefs on either side of the pedestal depicted Washington and a variety of revolutionary heroes in the wartime march to arms as well as the later movement to the West. At the front and back of the pedestal, allegorical groups of bronze figures represented America and sacrifices for her peace, freedom, and prosperity. The thirteen steps of the base on the lower level stood for the thirteen original states and led to four fountains at the corners of the base. Each of the fountains represented a different American river. The Hudson, Delaware, Potomac, and Mississippi rivers were surrounded by figures of Native people and by bronzes of their local fauna such as moose, bison, elk, and bear.

Siemering remained in Berlin and worked to make his complex design a reality, signing a formal contract in 1881. Recognizing the challenges of managing such an immense project at long distance with a foreign artist posed a challenge, the Pennsylvania Society sought the advice of the German consul in Philadelphia to find a gentleman in Berlin fluent in both English and German who might be willing to act on behalf of the Society. The consul’s recommendation drew into the monument’s story another interesting character—Kaiser Wilhelm II’s personal dentist, Alonzo H. Sylvester.

Sylvester was an American, born in Maine in 1857. He was one of many expatriates on the continent seeking his fortune. American dentistry, considered the most advanced, was in great demand in Europe at the time. Hoping to capitalize on the market, Sylvester had migrated across the Atlantic shortly following his graduation from Boston Dental College in 1871. He quickly built a prominent practice and attracted the attention of the royal family. Retained as the kaiser’s personal dentist, he was soon well known in Berlin society. His famous patron bestowed a number of favors on the dentist, including an honorary appointment as Royal Prussian Councilor. In 1882 Sylvester accepted the request to work on the Society’s behalf to guide the monument’s completion.

Even with Sylvester’s aid, progress was slow. One major cause of delay was the members’ uncertainty about where the monument should be placed. The most obvious location was Fairmount Park, an enormous urban park along the Schuylkill River. Several important memorials and monumental statues were already located in Fairmount Park, including a bronze statue of Abraham Lincoln dedicated in 1871. In March 1890 commissioners of the park authorized the placement of the Washington Monument at the entrance to the park at Green Street. That December, Pennsylvania Society leaders decided the Green Street site was no longer desirable, stating that the ground was “unsightly” and would require too much preparatory foundation work. Over the next several months, the Society requested one new site after another, wavering between several other locations in the park. By 1892 the Pennsylvania Society was ready to abandon Fairmount Park altogether and proposed to locate the memorial in the square directly in front of Independence Hall.

The decision pitted the Pennsylvania Society against an increasingly irate group of Philadelphia citizens, including the local chapter of the Colonial Dames of America. Some of those opposed to the plan believed the monument’s size and grandeur would distract attention from the restrained Georgian architecture of Independence Hall. Others feared that a monument so martial in character would overshadow the ideals associated with the iconic building. Angry editorials on both sides ran in Philadelphia newspapers. One especially irate writer—identified only as “A Countryman,” echoing the pamphlet wars of the early republic—went so far as to invoke the original controversy over the Society’s formation, stating: “Perhaps our ancestors were not so far wrong in fearing the effect of the Society of the Cincinnati upon the republic.”

The debate over the monument’s location was so contentious that it wound up in court. The opponents of the Independence Hall site alleged that the change would void the 1880 court decision that had merged the funds for the monument, since that petition had specified the location was to be in Fairmount Park. Spokesmen for the Pennsylvania Society responded that there was no more proper place for the monument than Independence Square, and that they had only abandoned Fairmount Park out of necessity. A series of legal battles and subsequent appeals carried on for over a year until the ordinance that gave the Pennsylvania Society permission to construct the monument in Independence Square was repealed by the city council in June 1893. The Society agreed to accept the Green Street site in Fairmount Park.

Critics also turned their attention to Siemering. Editorial writers asked why an American sculptor had not been selected to honor America’s greatest hero. Rumors spread that the sculpture was actually modeled after Frederick the Great, not Washington. Others referred to the monument as the “Prussian Invasion,” and the opposing counsel during the Independence Square court cases referred to Siemering as “that Hessian.” Trade unions in Philadelphia protested the idea that master craftsmen would be sent from Germany to oversee the monument’s assembly rather than using local workmen.

Internally, friction developed between the Pennsylvania Society, Sylvester, and Siemering. When granite for the monument arrived in Philadelphia in October 1893, the material needed for the base was found to be damaged. The Pennsylvania Society pressed Siemering for payment for the new material needed, but Siemering believed the shipping company should be held responsible for repairs. The argument dragged on for three years. The Pennsylvania Society’s legal counsel, William W. Porter, reported on his trip to Berlin in July 1896: “while Prof. Siemering may be a great artist, he is one of the most difficult men to deal with on a business basis that I have ever met.”

By that point, Sylvester and Siemering had fallen out over Siemering’s desire to gild portions of the bronze figures. The idea was not included in the original design and would have added significantly to the cost of the monument. Sylvester, moreover, did not care for the gilding. Recognizing Sylvester’s disapproval, Siemering sent his proposal to the Pennsylvania Society through another channel, while Sylvester privately advised the members to refuse the artist’s request. When the Pennsylvania leaders followed Sylvester’s advice, the sculptor angrily accused the dentist with meddling in his work.

Siemering’s work was finally completed in 1896, almost eighty-seven years after the resolution to create the monument. The sculptor shipped the finished bronze figures from Germany, and they were carted to Fairmount Park where they were carefully assembled. It was, a contemporary wrote, “the most imposing as well as costly monument ever erected to any American, with but the single exception of that monument of the same name at the National Capitol.” It was, at the time, the most expensive monument in the United States paid for entirely with private funds.

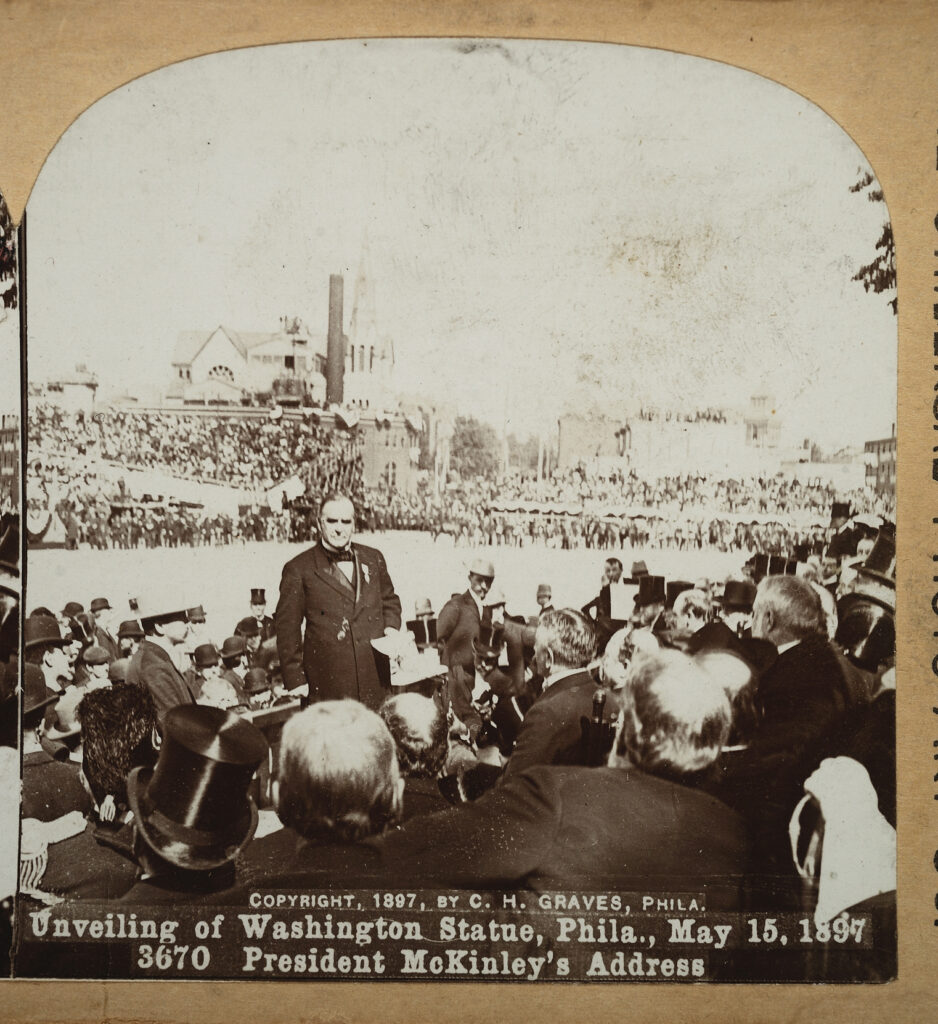

The monument was finally dedicated on May 15, 1897. The ceremony was the result of months of careful planning by a committee led by John Biddle Porter and William Macpherson Horner. The day of festivities was to include a formal dedication ceremony, a military parade, and a formal banquet. At their direction, a large grandstand was constructed opposite the monument along Fairmount Drive to accommodate as many guests as possible.

The guest of honor was President William McKinley. Other guests included Vice President Garrett Hobart; the secretaries of war, agriculture, the interior, and the treasury; the attorney general and postmaster general; the French ambassador; the governors of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey; the mayors of New York and Philadelphia; most of the Pennsylvania General Assembly; and thousands of ordinary citizens—far too many for the grandstands set up to accommodate. Also present was Alonzo Sylvester, newly installed as an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Society. Rudolph Siemering was conspicuous by his absence.

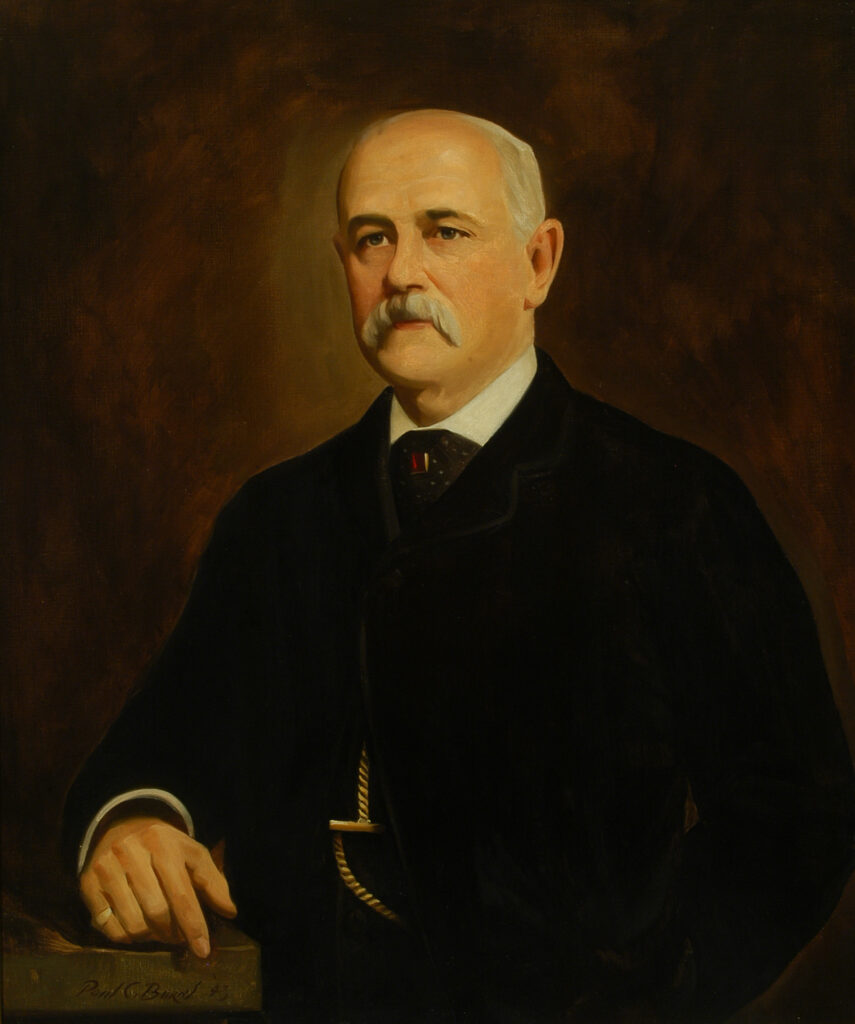

The president arrived shortly after two in the afternoon, wearing his own Eagle insignia as an honorary member of the Society of the Cincinnati. The First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry escorted McKinley to the ceremony at the head of a military parade, which later passed the president in review after he unveiled the monument. William Wayne, president of the Pennsylvania Society and recently elected president general of the Society of the Cincinnati, presided over the ceremonies, which began with an invocation by the Right Reverend O.W. Whitaker, Episcopal bishop of Pennsylvania.

President General Wayne then addressed the crowd, sketching the founding of the Society of the Cincinnati and the decision of the Pennsylvania Society in 1810 to build a monument to Washington. He mentioned Siemering as the sculptor, almost in passing. No one paid tribute to the Prussian sculptor’s extraordinary design, which until that moment had been hidden beneath two enormous American flags. His remarks concluded, Wayne escorted President McKinley and the trustees of the monument—Society members Richard Dale, Francis M. Caldwell, Dr. Charles P. Turner, and Harris E. Sproat—as well as the organizers of the event, John Biddle Porter and William M. Horner, across the street to the base of the monument.

As thousands watched in anticipation, President McKinley pulled a cord, releasing the flags and revealing the monument. The crowd erupted in cheers and a battery of artillery nearby fired a salute, which was answered by warships in the Delaware River. The party then returned to the reviewing stand, where the president delivered his dedication address. There was, McKinley began, “a peculiar and tender sentiment” connected with the monument. “It expresses not only the gratitude and reverence of the living, but it is a testimonial of affection and homage from the dead. The comrades of Washington projected this monument. Their love inspired it. Their contributions helped to build it. Past and present share in its completion, and future generations will profit by its lessons.” McKinley continued by offering a moving tribute to Washington.

He laid the foundation upon which we have grown from weak and scattered colonial governments to a united republic, whose domains and power as well as whose liberty and freedom have become the admiration of the world. Distance and time have not detracted from the fame and force of his achievements or diminished the grandeur of his life and work. Great deeds do not stop in their growth, and those of Washington will expand in influence in all the centuries to follow. The bequest Washington has made to civilization is rich beyond computation. The obligations under which he has placed mankind are sacred and commanding. The responsibility he has left to the American people, to preserve and perfect what he accomplished, is exacting. Let us rejoice in every new evidence that the people realize what they enjoy, and cherish with affection the illustrious heroes of revolutionary story whose valor and sacrifices made us a nation. They live in us, and their memory will help us keep the covenant entered into for the maintenance of the freest government of earth.

McKinley’s brief and eloquent remarks were followed by a long address by William W. Porter, a member of the Pennsylvania Society and a leader of the Philadelphia bar. He retold the story of the founding of the Society of the Cincinnati and presented a review of Washington’s life, comparing him at length to the heroes of antiquity, of the medieval world, and of more modern centuries. President General Wayne then presented the monument to the city of Philadelphia. In accepting the gift, Mayor Charles Warwick made a speech even longer than Porter’s, covering much of the same ground. He concluded by turning the monument over to the Fairmount Park Commission.

After the formal ceremonies ended, more than eleven thousand soldiers paraded by the reviewing stand. That evening the Pennsylvania Society hosted a banquet at Horticultural Hall in Fairmount Park, followed by fireworks and an illuminated bicycle parade. At the end of the evening, honored guests went home with a solid silver commemorative medal struck with the design of the monument and the date of the dedication.

Rudolph Siemering never saw his great monument to George Washington, but he completed other monuments in his native Germany. His statue of Wilhelm II and a large memorial in Leipzig celebrating German unification were widely praised. Both were destroyed in the Second World War. Alonzo Sylvester returned to his practice in Berlin until his death in January 1905. Siemering died less than two weeks after Sylvester.

The monument the Pennsylvania Society worked so long to create became a popular city attraction at the gateway to Fairmount Park. But cities, if they are healthy, are not static—even cities as old as Philadelphia. Growing adoption of the automobile, coupled with the popular “City Beautiful” urban redevelopment movement, prompted a proposal to create a broad landscaped parkway to unite a new museum district with downtown Philadelphia. During the initial planning phases, the memorial was left in its original location at Green and 25th streets at Fairmount Drive. But by the time the new parkway design was finalized in 1923, plans called for the Washington Monument to be moved to a dramatic position at the head of the parkway in front of the new art museum.

Though the total distance of the move was only about one quarter of a mile, the shifting of such a massive piece of art was no small task. The move was carried out by the O’Neill Company beginning in December 1925. Over the course of several months, each granite block in the monument was painstakingly numbered, and the monument was photographed from multiple angles to document any existing damage. Cranes and scaffolding were brought in to provide access to the heavy bronze figures while the surrounding layers of pedestal were removed. By October 1926, the monument had been completely reassembled in the newly created Eakins Oval in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which had been under construction since 1919.

The Society’s interest in the George Washington Monument did not end there. Though the monument was donated to the city upon completion, the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania has supported its maintenance. The Society provided funds for cleaning and conserving the monument for its one hundredth anniversary in 1997. The monument remains today as a testament to the determination of the Pennsylvania Society and its dedication to the injunction in the Institution to perpetuate the memory of the American Revolution and its heroes.