In the spring of 1783, after enduring eight long years of war, the main part of America’s Revolutionary army was camped along the Hudson River in New York waiting for word that a peace treaty had been signed. The soldiers—officers and enlisted men alike—had not been paid in months, in some cases longer, and feared being sent home without their pay. Rumors spread that the soldiers would march on Philadelphia to force Congress to pay them or would even try to establish a military dictatorship.

Instead, the officers banded together to form an organization that would honor their fight for American independence while providing support for their common struggles. On May 13, 1783, the group was founded and named the Society of the Cincinnati, after the ancient Roman hero Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus. More than 2,200 officers joined the Society and pledged themselves to its principles: commemorating the achievement of American independence, preserving the union of states that resulted, and maintaining the bonds of friendship forged in war. George Washington became the Society’s first president general, leading his officers from war to peace.

The Society of the Cincinnati embodies one of the most important legacies of the Revolutionary War—that Americans who had left their homes to fight for their country were willing to abandon their swords and support the subordination of military power to civilian rule. Theirs is the story of how the war ended, what happened next, and how an armed revolution gave way to a civilian republic.

The Secret History of the Society of the Cincinnati told these stories—as the Society turned 225 years old—through more than thirty works of art, artifacts, manuscripts, and pamphlets. The highlight of the exhibition was the Society’s founding document, known as the Institution, which had never before been on public display. It was joined by important objects lent by other institutions, including Henry Knox’s manuscript draft of the Institution written in April 1783 (The Gilder Lehrman Collection, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History) and Ralph Earl’s full-length oil portrait of Benjamin Tallmadge, wearing his Society insignia, and his young son William (Litchfield Historical Society).

Attributed to Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807)

ca. 1775

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Margaretta Kingsbury Maganini, 1969

The Society took its name from the ancient Roman hero Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus. In the fifth century BC, Cincinnatus was twice called out of retirement to lead the Roman army against foreign invaders. Both times he refused to accept rewards or power and returned to his farm, becoming a symbol of selfless patriotism that was well known into the eighteenth century. The Society’s name honored the sacrifices of its members, who, in the model of Cincinnatus, left their homes to fight for their country then humbly returned to their civilian lives. This oil painting of Cincinnatus is attributed to Angelica Kauffmann, a native of Switzerland who specialized in portraits and classical scenes.

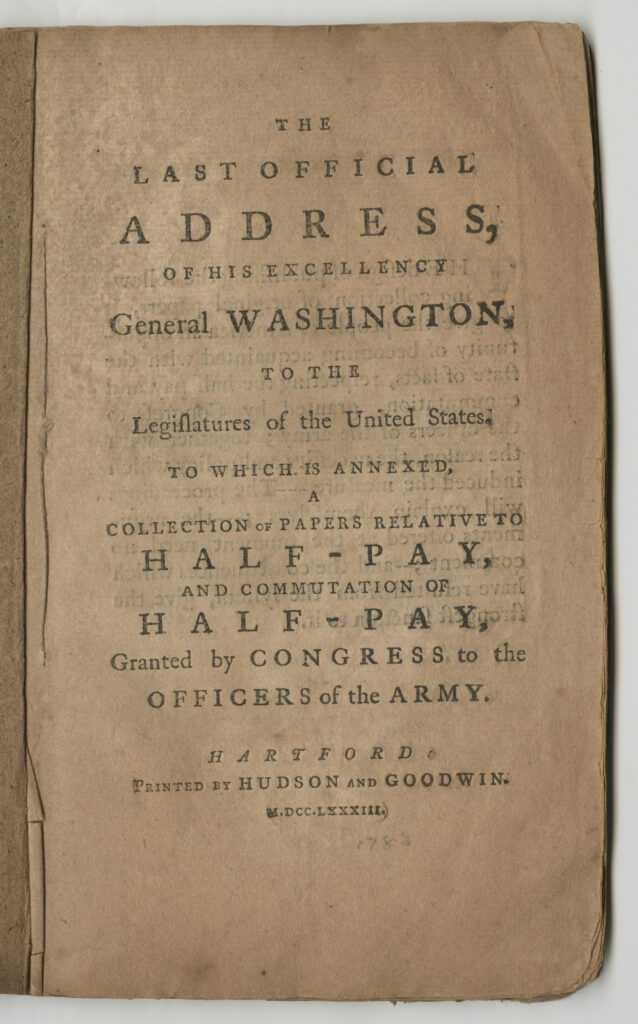

Hartford: Printed by Hudson and Goodwin, 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Over the winter of 1782-1783, Maj. Gen. Henry Knox led a failed effort to lobby Congress with petitions while Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall of New York and Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates of Virginia conspired to lead the army to mutiny, threatening not to disband until the officers were paid. To inspire officers to follow them, the generals chose Maj. John Armstrong, Jr., of Pennsylvania, one of Gates’s aides-de-camp, to write the Newburgh Addresses anonymously. The series of letters laid out the plight facing the officers—the “cold hand of poverty” they felt—and challenged them to meet to take the next steps. The addresses were first printed in Fishkill in March 1783. Washington put an end to the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy with an emotional appeal to the officers for patience and loyalty, ending with his admission, “I have grown gray in your service.” This edition, printed in Hartford in June 1783, joins Washington’s speech that month with the earlier Newburgh Addresses.

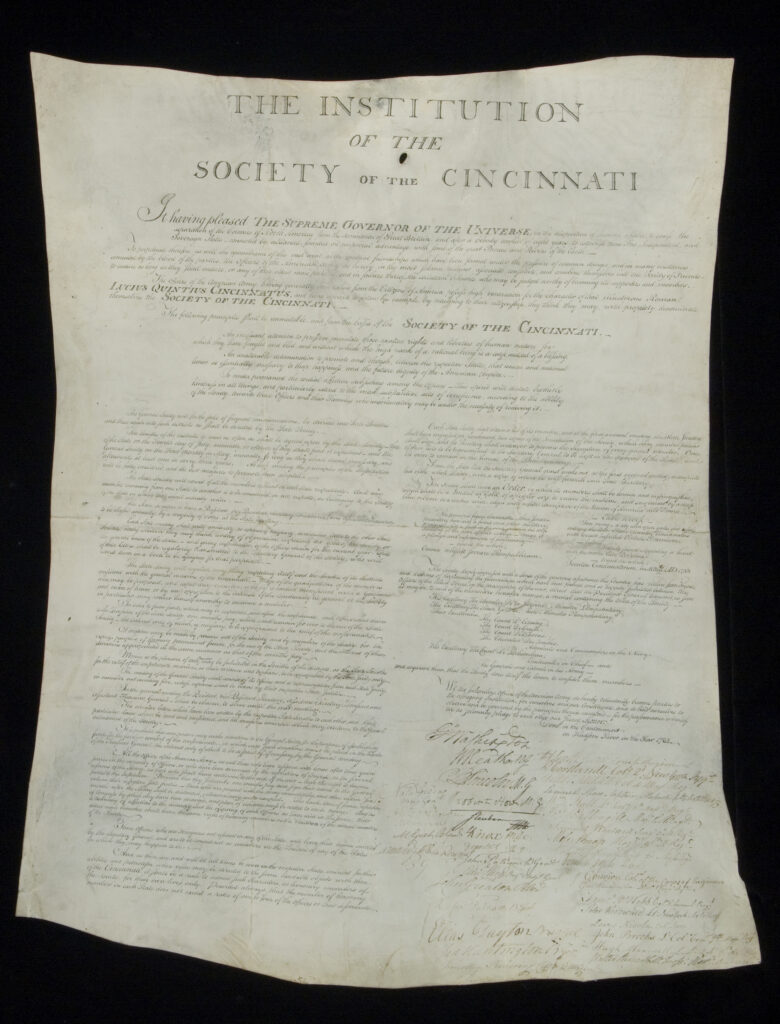

May 13, 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

In April 1783 Henry Knox drafted a constitution for a national society of officers that would maintain their fellowship and protect their common interests after they returned home. Knox envisioned a hereditary society of American officers of the Continental Army whose membership would pass to their eldest male heirs. In addition to preserving the memory of the Revolution, the society would establish treasuries to support veterans and their families. On May 13, the general officers and representatives of the state regiments gathered at Steuben’s headquarters in Fishkill, New York, and formally established the Society of the Cincinnati. The meeting directed that the founding document, called the Institution, be inscribed on parchment and taken to George Washington in Newburgh for his signature “at the head of it.” The signatures of thirty-five fellow officers follow his.

Thomas Benjamin Pope (1834-1891)

Mid-19th century

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Katharine McCook Knox, 1973

George Washington made Hasbrouck House his headquarters from March 1782 to August 1783. From this house built by Huguenot immigrants in 1750, Washington rejected a suggestion that he become king after the war, issued the first Badge of Military Merit (the precursor to the Purple Heart), and became the first to sign the Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati. This oil painting of the house was done by Thomas Benjamin Pope, a Hudson River School artist who settled in Newburgh, New York, prior to the Civil War.

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant (1754-1825)

1783

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

Maj. Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, a veteran of the Continental Army’s Corps of Engineers and original member of the Society, designed the organization’s insignia, known as the Eagle, in June 1783. His watercolor drawing of the insignia calls for a double-sided gold medal in the shape of an American bald eagle, bearing images of Cincinnatus on both sides and suspended from a blue-and-white ribbon—the colors “descriptive of the Union of America and France.” The Society’s leaders approved the design on June 19, 1783.

Nicolas Jean Francastel and Claude Jean Autran Duval, Paris, France

1784

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Harrison Tilghman, Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland, 1953

Believing that no craftsman in America was capable of making a gold medal as fine as the Society Eagle, L’Enfant sailed to Paris in the fall of 1783 to employ French craftsmen to make the first Society insignias. He took with him subscriptions from about forty American members who had placed orders for an Eagle at a cost of forty dollars each. By spring 1784, Parisian craftsmen Nicolas Jean Francastel and Claude Jean Autran Duval had made a total of 225 gold-and-enamel Eagles, most of which L’Enfant delivered to America. This example is one of seven ordered by George Washington for former aides-de-camp who were also original members of the Society. The Eagle was owned by Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman (1744-1786) of Maryland and retains its original silk ribbon and metal clasp.

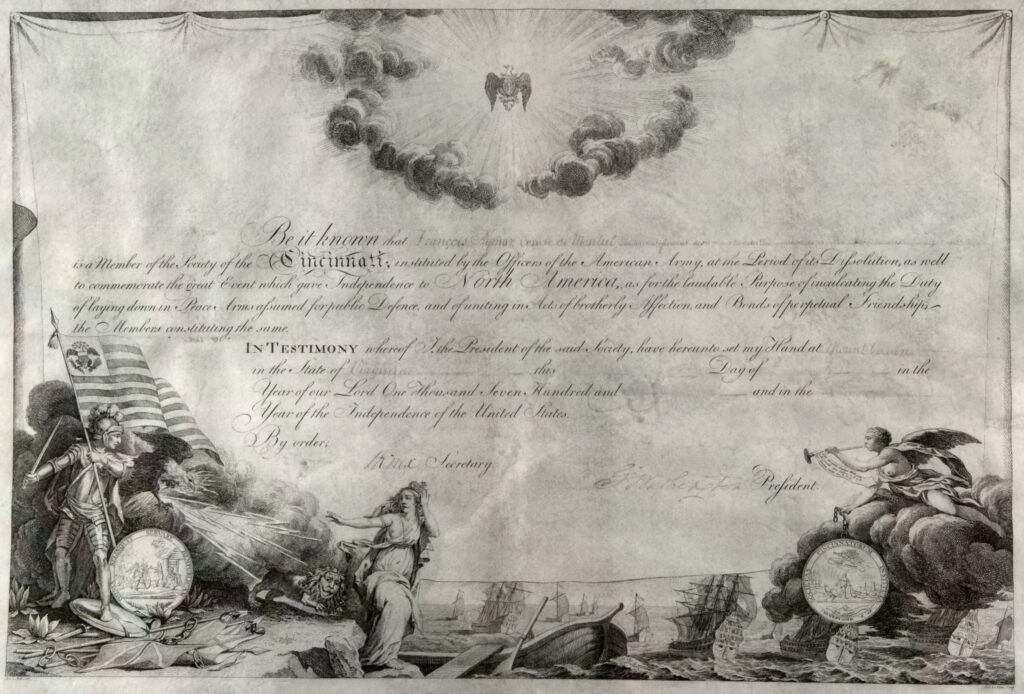

ca. 1789

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Original members could also purchase a Society membership certificate, known as the diploma, designed by Pierre L’Enfant. On the left, a soldier in armor representing America steps on captured flags while a bald eagle shoots lightning bolts at a cowering lion and figure of Britannia, who retreat towards a British fleet fleeing America’s shores. On the right, the figure Fame proclaims the American victory and independence, while the Society’s Eagle insignia radiates over the scene. While in Paris in early 1784, L’Enfant commissioned a copper plate of his design for use in printing the parchment diplomas, which would be done in Philadelphia. This diploma attests to the membership of François Aymar, comte de Monteil (1725-1787), a lieutenant général in the French navy. He died before receiving his diploma, so it was sent to his son with a letter from Admiral d’Estaing, the first president of the French branch of the Society.

Thomas George and Daniel King, Jr., Philadelphia

1787

The Society of the Cincinnati Archives

During the Society’s second general meeting in Philadelphia in 1787, the group had this mahogany document box made to hold the Society’s growing archives of minutes, correspondence, and other documents, including L’Enfant’s drawings for the Society emblems. The Society paid Thomas George three pounds for the box and Daniel King, Jr., seventeen shillings for the engraved brass plate. The document box and its contents were initially the responsibility of each secretary general.

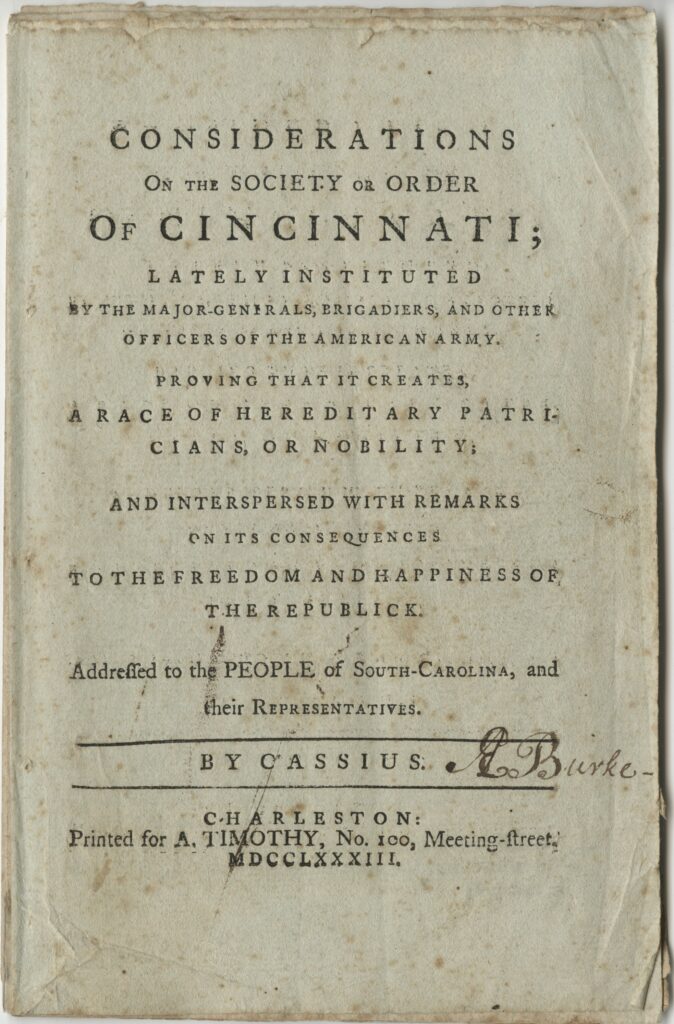

Aedanus Burke

Charleston, [S.C.]: Printed for A. Timothy, 1783

The Society of the Cincinnati, Library Acquisitions Fund purchase, 2004

Writing under the pseudonym Cassius, Aedanus Burke, a South Carolina judge, published his criticisms of the Society in this pamphlet printed in October 1783. Burke charged that the Society would create a hereditary nobility, which would destroy the nascent American democracy. He encouraged state legislatures to pass resolutions opposing the Society. Burke’s attack became popular enough to be reprinted in numerous American and European cities and to inspire the publication of several responses written by defenders of the Society.

Winthrop Sargent

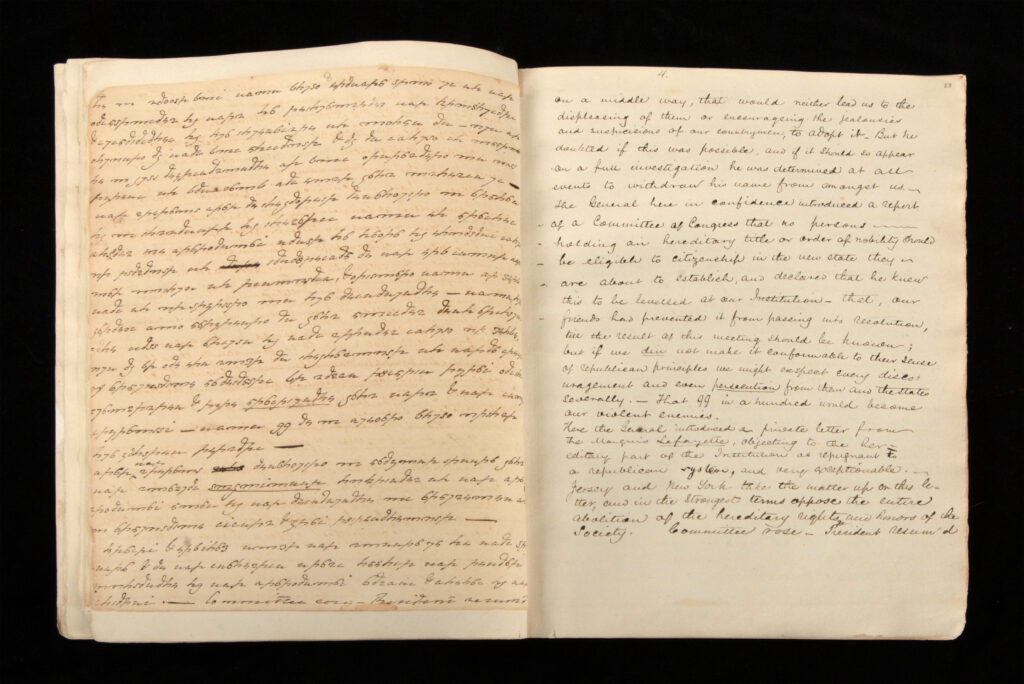

May 4-17, 1784

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Dudley Phelps King Wood, 1959

When the Society gathered for its first general meeting in May 1784, its business was primarily to address the controversy stirred by Aedanus Burke’s pamphlet. George Washington presided over the meeting and proposed numerous changes to the Institution in response to opposition to the Society—striking every “political tendency,” abolishing the hereditary principle of membership, and giving control over each state branch’s treasury to that state’s legislature. In the face of Washington’s threat to resign his office if these changes were not made, the meeting agreed to revise the Institution. Newspapers soon printed the text of the amended Institution, but it never took effect because not all of the state branches ratified it. Maj. Winthrop Sargent, a delegate to the meeting from the Massachusetts branch, kept this journal of the proceedings in code, perhaps to protect the Society from further criticism. This opening shows the original text in code on the left and the translated text deciphered in 1847 on the right.

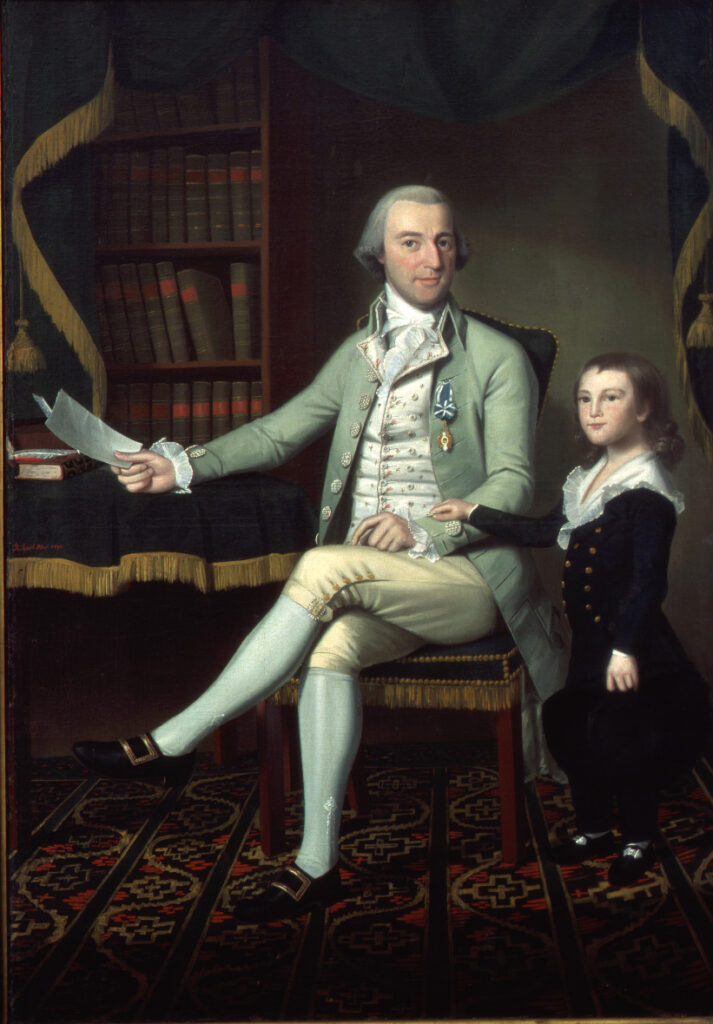

Ralph Earl (1751-1801)

1790

Collection of the Litchfield Historical Society

Benjamin Tallmadge (1754-1835) was one of the original members of the Connecticut branch of the Society of the Cincinnati. He had distinguished himself during the Revolution as an officer of the Continental Light Dragoons and leader of George Washington’s intelligence service. After the war, Tallmadge settled in Litchfield, Connecticut, where he opened a general store, invested in real estate ventures, and was elected to Congress (1801-1817). His wealth and prominence, as well as his Society of the Cincinnati Eagle, are on display in this portrait by Ralph Earl, an American artist trained in London during the war. Tallmadge’s son William, five years old at the time, serves as a reminder of Society members’ hopes to pass on to the next generation the memory of the American Revolution.

Paris, France

18th century

The Society of the Cincinnati, Gift of Fairlie Arant Maginnes, 1994

This porcelain soup plate was originally part of a set of six given to Maj. James Fairlie by Baron von Steuben in gratitude for Fairlie’s service as Steuben’s aide-de-camp during the Revolutionary War. Both officers became original members of the New York branch of the Society. After the war, Fairlie settled in New York City, where he became the first secretary of the Bank of New York and clerk of the New York Supreme Court. Steuben was voted an American citizen in 1784 and settled in Utica, New York, on land granted to him for his military service.

ca. 1784-1785

The Society of the Cincinnati, The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection

Claude, chevalier de Chavagnac (1740-1812), was among the more than two hundred veterans of the American war to join the French branch of the Society. He had served in Admiral d’Estaing’s squadron along the East Coast and in the Caribbean as a lieutenant de vaisseau. In this oil portrait, painted by an unidentified French artist, Chavagnac is depicted wearing a full dress naval uniform with medals of the Ordre de Saint-Louis and the Society of the Cincinnati on his chest and his family crest in the upper left.